Inequality Readers. Decoupling

Affluence consumption decouples. Whose parents in the couple matters? Prices and costs.

Affluent Consumption Decouples from the Rest

I found this working paper to be fascinating. It covers an extremely viral and buzzy topic: the imputation of missing individual-level consumption data with zip-code medians. Ooh. You can faintly hear in the background Derek Thompson fighting with Ezra Klein over who gets to cover this viral story first!

They begin with a common researcher problem: how to handle missing data on your topic of interest - in this case, consumer spending.

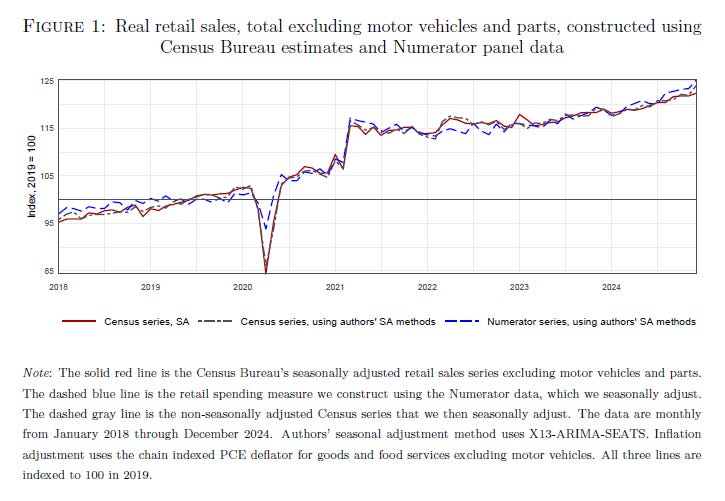

They compare data from two sources: Numerator, a consumer dataset, and the Census MARTS data:

Hey, who else is excited to learn about a new Census data source ?!

A description of the Numerator data:

A description of the Census MARTS data:

The purchase information from each:

Consumption data from the two look very similar in the aggregate

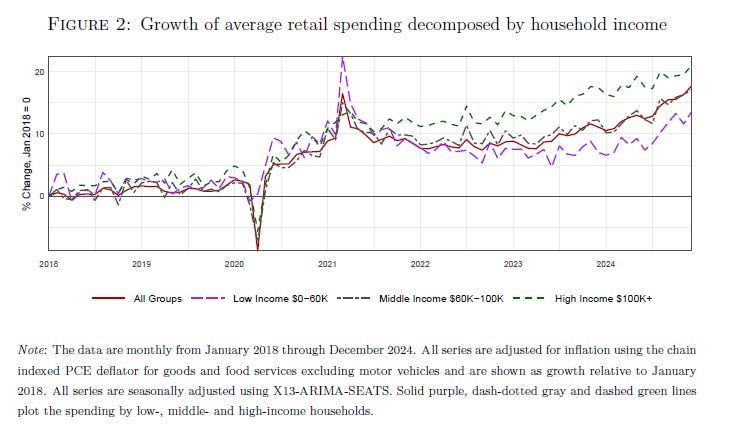

Here’s where things become neat. Let’s look at spending by income groups - high, middle, and low.

The growth of spending of the three groups was very similar from 2108 to around the middle of 2021. Since then, high income spending (green dashed line) has outpaced the spending over everyone else. In fact, lower and middle income group spending has basically been stagnant between 2021 and 2025.

But when using aggregated zip codes split into high, medium, and low, we see a very different story:

Total overlap. That’s because lots of low / middle / high income folks don’t live in low / middle / high income zip codes.

In 2024, only around 60% of low income folks lived in low income zip codes.

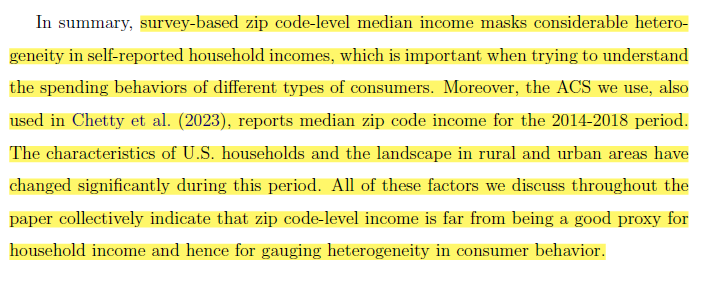

So if we’re using zip codes to try and learn about socioeconomic differences, we’re probably missing the mark:

Cool methodological point. Also - I suspect that we’re seeing the return of inequality. Stabilized, moderately declining inequality had a good run.

Couples Inherit Parents’ Earnings from their Husbands

I’m a big fan of Wen Fan and Yue Qian, and so I was happy to see this co-authored article by them.

There is intergenerational similarity of the balance of earnings within couples (e.g. husband breadwinner, husband earns 40% of total income, wife earns 20%, etc.). In straight couples, do their earnings mixture look more like the family of the husband or the wife?

Fan and Qian use the Panel Study of Income Dynamics, which includes earnings information of couples and one of their (husband or wife, not both) parents.

The main outcome is a proportion, 0 to 1, of the total couple’s earnings made by the wife.

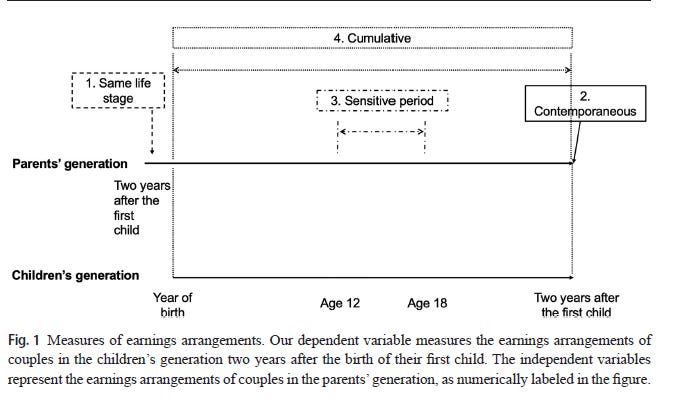

The main predictor is a proportion, 0 to 1, of either the husband’s or the wife’s parents. When to measure this proportion? Fan and Qian examine a couple of different potentially important stages of life:

Right when the child is born, between 12 and 18, and at the same time as the child generation’s earnings are measured.

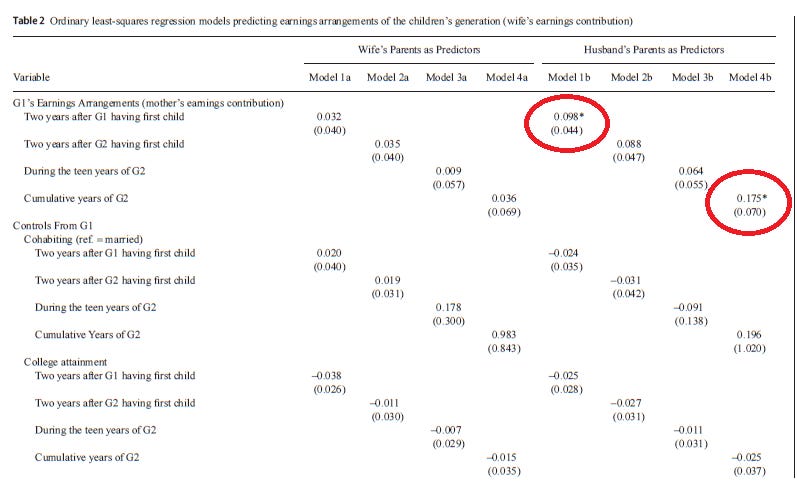

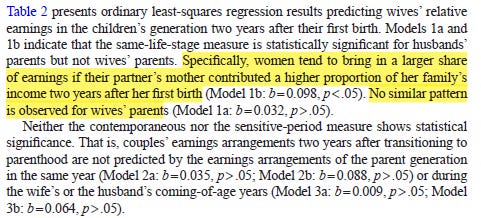

What do they find?

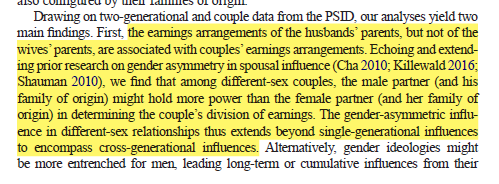

Not a ton of association between the wife’s family and the wife’s arrangement. However, the husband’s family arrangement matters - husbands coming from families with a higher share of wife’s earnings also end up in couples where the wife earns a higher share of the income.

Also - they only find meaningful associations from the early life stage.

Their overall assessment:

I would have loved to have seen a study of heterogeneity. Specifically, zero earners. I wonder how much of this is: husband who grew up in single earning household ends up in a single earning household. Further, given that they find that the meaningful timing is around birth, I would assume a lot of this has to do with … fertility! How much heterogeneity do we see surrounding family status of the child’s generation? As always, more interesting work to be done!

Universal Basic Income Doesn’t Do Anything for Child Development

A bummer of a finding, but good to know!

Early life matters, and early life income is shown to be highly consequential for children’s outcomes:

This seems like the perfect context to examine whether an increase in cash has a causal effect on these overall associations. It could be the money, it could be something else.

There exist pseudo-experimental situations of policy change that are beneficial for child outcomes, but they don’t get exactly at cash:

The study took place in three ok cities, the greatest city in the world, and a city that is probably very jealous because it’s right next to the greatest city in the world:1

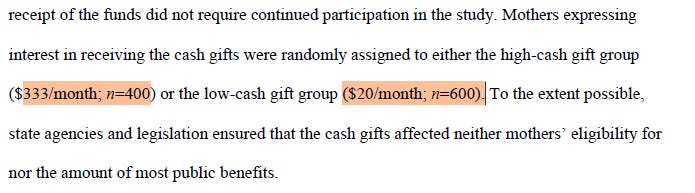

So we have poor mothers as the sample. They received either $333 / month or $ 20 / month:

It seems that the authors tried to make sure the increased income did not affect eligibility for public benefits, but the details are fuzzy as written. The money was given over 48 months, when the study ends, resulting in either ~$16,000 or ~$1,000 over four years.

The outcomes the authors are interested in assessing deal primarily with language, cognitive, and social - emotional development:

An example of one of the items:

After all that, what happened? Nothing.

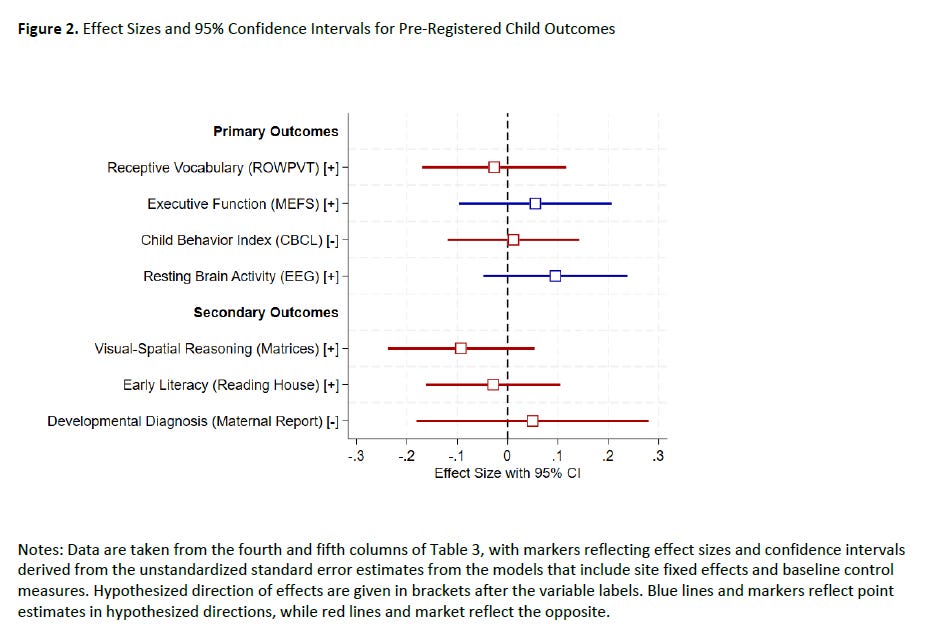

Those squares are effect sizes of being in the “big cash” group compared to being in the “little cash” group. The vertical zero line, if included in the vertical red and blue bars, suggests that we cannot differentiate the found effect size from a zero effect size. And that … is what happened.

Lots of testing and poking and prodding after this. All resulting in … a zero effect.

The summary of the authors’ conclusion? Bummer! They try and figure out why no effect was found. One interesting point - these transfers were large.

Of course, this experiment was being conducted during a set of other mass society experiments - the whole pandemic and pandemic response nonsense of 2020 onward:

I find the “in favor” more compelling than “arguing against.”

Overall, this study probably should pump the brakes on the idea that universal basic income (ubi) will solve all our problems. That said, I did have a few lingering thoughts:

I didn’t see them talk about their own sample selection: poor mothers. Perhaps ubi has a big effect on those just slightly not poor. Or perhaps there is effect heterogeneity among those in extreme poverty. Totally fine to focus on a particular slice of folks, but it doesn’t provide an answer to all folks!

Does ubi have less bang for its buck in big cities, or in big blue cities? Anyone on the internet these days probably knows about the massive cost of living problems of places like large blue cities. Maybe we see underwhelming results in NYC, or in all these cities, but would find positive effects of folks living in smaller places.

Local and state policies create lots of heterogeneity. Are null effects mostly due to null effects in NYC and the Twin Cities? I also wasn’t totally sure whether the authors’ claims that these cash transfers did nothing to other government assistance. How confident are we in that?

Children who live in Saint Paul tend to be deeply extraordinary on all metrics. Perhaps including this crown jewel of the American experiment biased results in odd ways (I’m kidding! I live in Saint Paul).

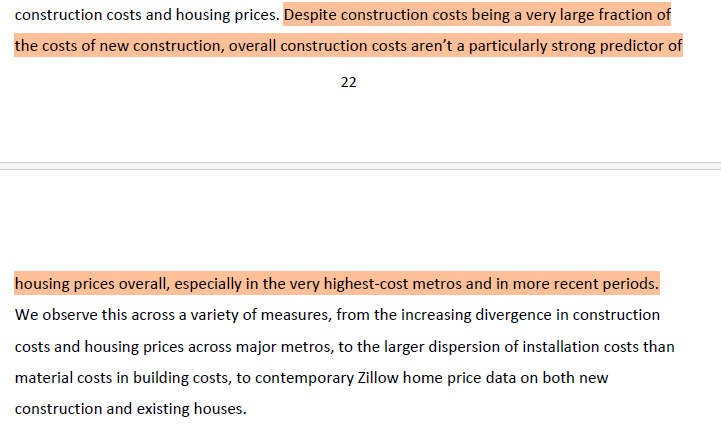

Building Costs Don’t Drive Housing Prices

I’m including this paper because I am a big fan of Brian Potter’s Construction Physics substack. And it is an interesting paper that helps identify the culprits of high housing prices.

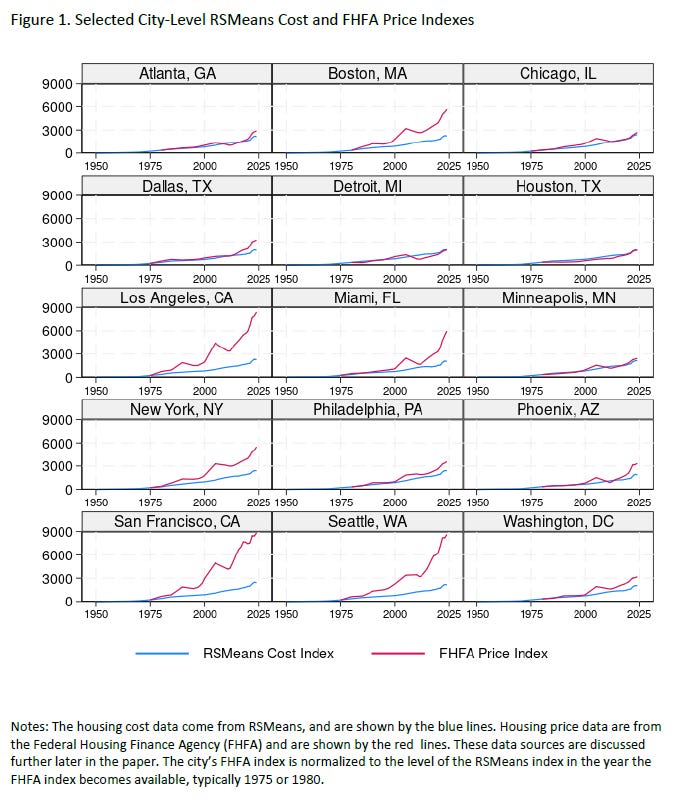

Here’s a big payoff to this paper: we really don’t see a big link between construction costs (blue lines) and housing prices (red line), especially in those cities that are the biggest culprits of housing affordability.

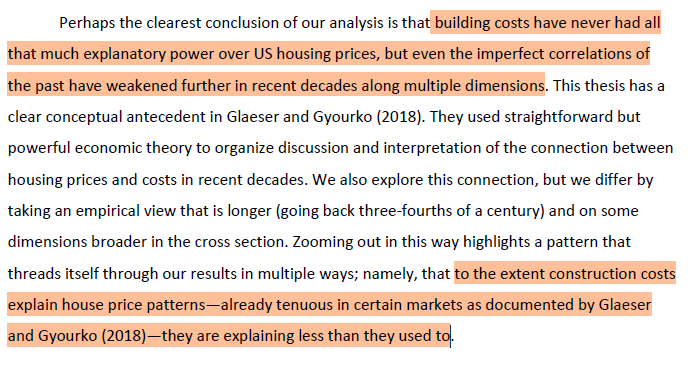

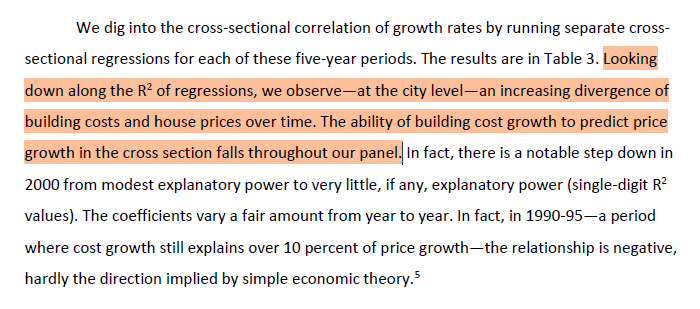

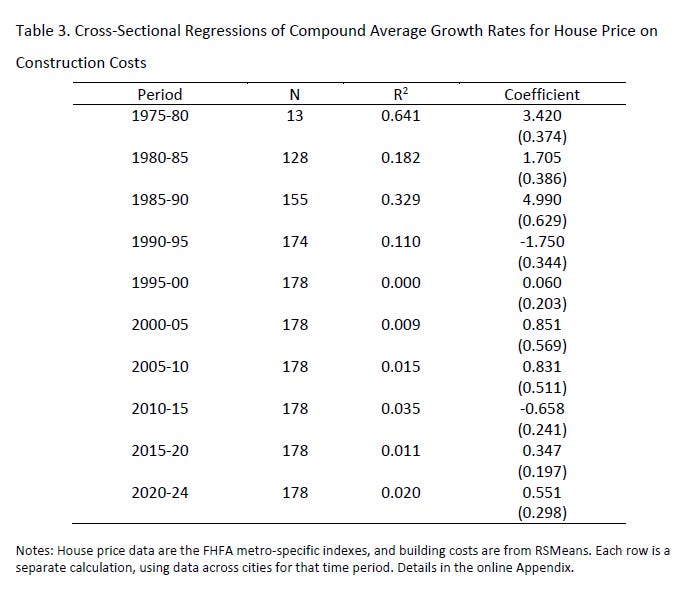

The paper’s big point: whatever weak input construction costs had to housing prices has broken further down in the present day:

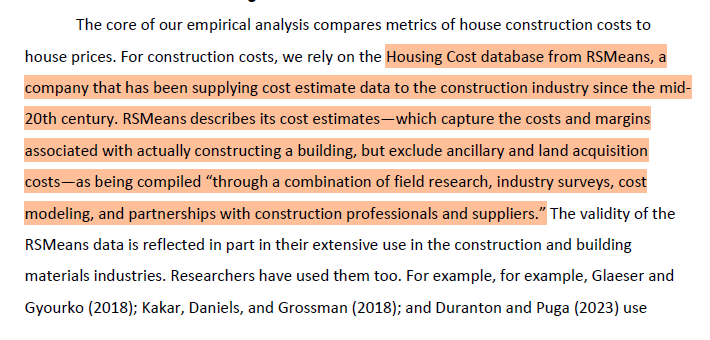

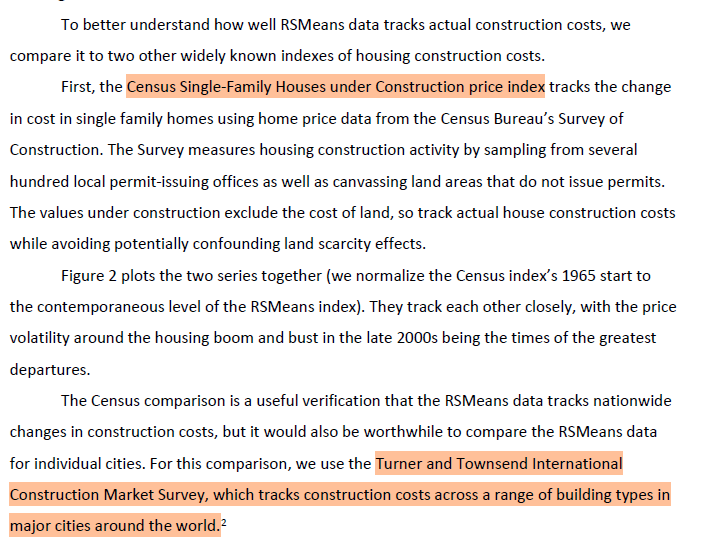

The authors use a private dataset, RSMeans, to collect construction cost estimates:

And they compare it against aggregate Census data, and another private data source, of construction costs, to ensure its accuracy:

RSMeans and Census give you the same trends

Looking over time, construction costs break down in their explanatory power of housing costs:

Basically: chunk the data into five year groups. Then examine the association between construction and housing costs. We see the coefficient (right panel) decline from high and positive to small). And we see the amount of variation explained by construction costs (R2) decline from pretty big (e.g. 0.182) to very small (e.g. 0.02).

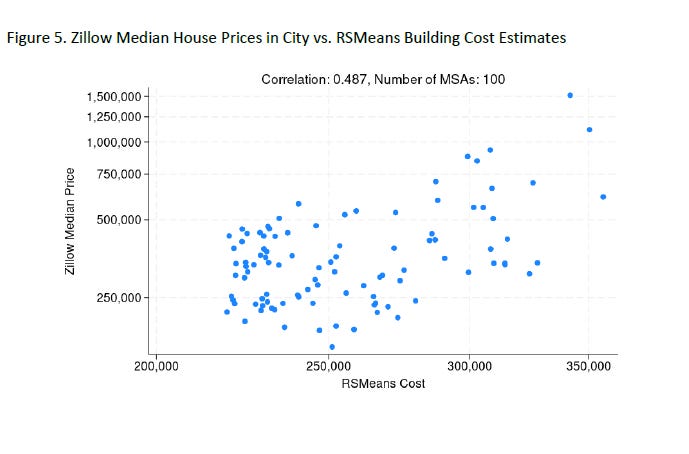

If we just look cross-sectionally (e.g. ditching issues of change and growth), we do see a pattern between costs and prices.

That said, there is still a lot of heterogeneity, and there are lots of confounding factors that will affect these point-in time costs and prices. So this isn’t really a strong counterargument to the trends.

Basically - don’t turn to construction costs if you want to lower housing costs, especially in the most expensive cities:

I live in Saint Paul, MN, by the way.