Sociologists BK Lee and Bernice Pescosolido (LP) published an intriguing article last year on the link between suicide and economic context.

We begin with a basic observation: work matters for health.

And critical for their study - unemployment is a big risk factor for suicide:

But - following the Great Recession, unemployment risk went down, and suicide risk went up. What’s going on?

LP ask us to turn our attention to this guy:

Durkheim is a famous classic theorist who wrote some of the founding empirical work on the link between social cohesion and suicide. Unemployment’s link to suicide is not merely through economic strain, but also through social integration and stigma:

Unemployment not only produces economic hardship, but it loosens to bonds between a person and their social context, it produces stigma, ups the risk of discrimination (unemployed may be viewed as lazy or incompetent), sours a person’s view towards the future, alters a person’s social connections, “loosens their regulative bonds towards society” (I love this phrase - basically, think of it as undercutting the pressure people feel towards conforming to pro-social behavior), and generally “shatter[s] existing norms and social structures.”

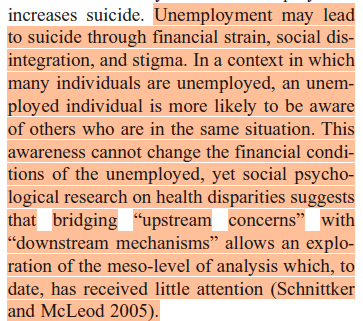

This is all to say: unemployment doesn’t just produce suicide through economic mechanisms. We also need to think of the social, of connection, and of context. That old theorist above, Durkheim, famously talks about social connections and social integration - too much or too little - as a key predictor of suicide. LP say: let’s take this social connection concept seriously and conceptualize sameness:

Social ties occur via homophily (birds of a feather flock together). People also are aware of their surroundings! They may sense whether they’re in this together with a lot of other unemployed people, or whether they’re in it alone. So - unemployment may mean something very different whether (1) you’re living in booming Seattle or (2) you’re living in stagnating Cairo, IL and (3) whether the country’s going through a massive economic crisis.

LP assemble a dataset of suicide across 37 states and 13 years, 2005 - 2017:

They look at unemployment context at both the county and commuting zone levels (commuting zones are basically metropolitan statistical areas popularized in sociology by *ahem* yours truly).

Since suicide is a rare event, they merge the rates of suicide from the NVDRS to larger census data. And since suicide is a rare event, “adding” these NVDRS data to census data functionally change nothing for our population counts in counties or commuting zones. A clever idea!

They measure contextual unemployment as the percent unemployed in a particular commuting zone, and they look at occupational information on death certificates in the NVDRS:

Then, LP construct sameness measures that match the proportion of a place with the same employment status as those who commit suicide:

The authors estimate fairly standard multilevel regression models to assess suicide rates. And we get predicted rates of suicide in places given the employment status if the individual and the broader economic conditions.

We start with a descriptive puzzle: unemployment peaked then declined following the Great Recession, while suicide among the unemployed basically underwent a seculary rise from 2012 onward:

Here’s a big finding: notice the ever-so-slight slope of the line in the middle figure:

Just kidding. It’s an obvious slope! Suicide rates among the unemployed look pretty darned similar to the employed in places where unemployment is high. But where unemployment is low, the unemployed have very high suicide rates.

“Sameness” really matters for the unemployed. More alignment between one’s unemployment and the broader unemployment in their place, lower suicide. We don’t see nearly as much sameness alignment for the employed, or those not in the labor force:

Here’s a wrinkle: macro-economic conditions kind of smooth out the local effect of unemployment:

Let’s look at the top left and bottom right figures in turn. The top left basically constructs that middle slope we focused on earlier for every year in their data. We see that the Great Recession basically _removed_ any local sameness effect. Then when the economy started really heating up in the post-2012ish period, local sameness effect really went into overdrive.

Now the bottom right: we’re looking at national unemployment on the x-axis, and local sameness effects on the y-axis. In better economic times (lower national unemployment), local economic conditions really matter: big gaps in suicide between the unemployed in locally good and bad markets. When national unemployment is high (like the Great Recession era), local economic conditions are much less consequential. So - something like the Great Recession suggests that it’s not so uncommon to be unemployed. Economic times are terrible!

The authors’ big picture summary of their findings:

So unemployment is a big predictor of suicide - but unemployment doesn’t just predict suicide the same everywhere. Less sameness, bigger risk.

I really love this study. It will probably be an example in my intro to sociology class for a long stretch into the future. It is almost a textbook update to C Wright Mills’ definition of the sociological imagination, which asks for the dual consideration of history and biography, or the broader social context and the individual circumstance. And so we see a biography of unemployment ending up with very different risk factors depending on the contextual history in which it is embedded. Cool!

Rich People are Leaving

Since we’re talking about the importance of place, let’s look at how places have changed after the pandemic. There’s a fascinating recent NBER paper by the Nicholas Bloom team. Bloom is a big work-from-home advocate in the economics world.

Their goal:

The data they use:

Part of me is very impressed that they were able to obtain and use these data for research purposes. Another part of me deeply hates this world of massively invasive proprietary private data that is constantly being harvested from us.

When Gusto data aren’t available, they use their own survey:

They outline their main findings. After the massive data lift, the findings are fairly descriptive and elegant:

Then:

Then:

Interestingly:

This relocation paid off:

Next:

Let’s take a look at their striking findings.

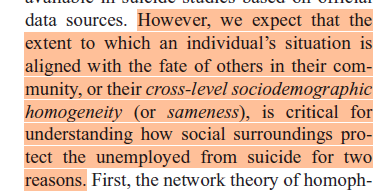

Workers live farther from their employers now - the pandemic created a genuinely new trend of greater distance between work and home:

An increase mean distance from about 15 miles in 2019 to about 28 miles in 2023. The percent of folks living very far away (50+ miles) increased from about 4% to almost 10%

It’s a new-hire thing. Folks already locked down in 2019 (yellow line) didn’t have massive relocations. New hires (blue line) drive the trend.

It’s the older young adults and younger middle aged adults who are driving this trend:

This makes sense to me. I assume that moving farther away from work functionally means moving to an exurb, or to a small town, or away from the city core. Folks in these age brackets are more likely to have kids, and work from home (1) allows bigger houses (2) allows better connection with certain schools (3) potentially allows for more productive in-person childcare. At the same time, cities had a very real problem of increased crime, car jackings, disorder, poor governance, and poor cost of living. It is completely sensible that you might see large numbers of parent-aged folks choose to relocate.

Who is driving this large gap between home and work? Higher income people:

Look at the graph long enough and you’ll notice an ever-so-faint gap in work from home between high income workers ($250k+) from less high income workers (100-250k) to everyone else. So the rich are leaving.

We see higher income workers moving to lower tax states.

I did a brief re-skim of the article, but didn’t see the following point mentioned: notice that the higher income relocation began in 2018? A pre-existing trend got walloped by the pandemic. Could this be due to the 2017 tax change that affected local tax deductions based on housing value? I’d guess so.

There is a lot more I’d like to know. Where are these high income workers moving? Are we seeing a relocation to an isolated forest mansion, a high income enclave in Nashville, or to becoming a big fish in a lower income small town pond?

My worry is that we are going to see economic segregation occurring on overdrive. And a more general trend of isolation, segregation, and extremism driven by compensation with online / social media activity. Of course, people could be moving to community or to extended family, which would cut against my worries. A lot more work is needed here.

I will just leave this little nugget here: are higher income, and higher status, Americans facing a crisis of civic responsibility?

Briefly - Durkheim and Suicide Clusters

If you’re interested in the sociological study of suicide, or social theory rooted in Durkheim, I really recommend the book Life under Pressure: The Social Roots of Youth Suicide and What to Do About Them by Mueller and Abrutyn (MA).

The book’s official description:

Youth suicide clusters have deeply unsettled communities in recent years. While clusters have been widely documented in the media, too little is known about why youth die by suicide, why youth suicide clusters happen, and how to stop them both.

In Life under Pressure, Anna S. Mueller and Seth Abrutyn investigate the social roots of youth suicide and why certain places weather disproportionate incidents of adolescent suicides and suicide clusters. Through close examination of kids' lives in a community repeatedly rocked by youth suicide clusters, Mueller and Abrutyn reveal how the social worlds that youth inhabit and the various messages they learn in those spaces--about who they are supposed to be, mental illness, and help-seeking--shape their feelings about themselves and in turn their risk of suicide. With great empathy, Mueller and Abrutyn also identify the moments when adults unintentionally fail kids by not talking to them about suicide, teaching them how to seek help, or helping them grieve.

Through stories of survival, resilience, and even rebellion, Mueller and Abrutyn show how social environments can cause suicide and how they can be changed to help kids discover a life worth living. By revealing what it is like to live and die in one community, Life under Pressure offers tangible solutions to one of the twenty-first century's most tragic public health problems.

I read this book a year ago, so bear with me. 10,000 foot overview. MA spend a very long time investigating a “suicide cluster,” or a place where a disproportionate number of young people commit suicide. The place sounds a bit like a wealthy suburb of Indianapolis and wouldn’t necessarily be expected to have this serious problem. MA are pretty great at applying the deeper insights of Durkheim’s suicide theory to this case, and they about about examining the overly-tight social cohesion of their case, with its corresponding social pressures and expectations, which ultimately ends up with this massive social problem.

If you’re interested in this topic, or in how classic theory can be very nicely applied to a modern case, or if you want an in-depth case study of the link between individual outcomes and broader social context, I recommend! It is one of those books that I will occasionally think about, even a year after reading.