Why does human society have stratification? This is a bit of a different kind of question than is normally asked these days. We often think about the amount of inequality - e.g. why is Jeff Bezos so much richer than the typical Amazon employee than Raymond Kroc was of the typical McDonalds employee back in the 1950s.

But why does stratification across people exist in the first place? It’s an interesting question and one that is surprisingly relevant and consequential.

Here we have the interesting essay by Ralf Dahrendorf.

Let’s have wikipedia give a 10,000 overview of RD:

I’ve read RD’s greatest hits and hit most prominent book:

But I hadn’t encountered this essay before.

RD says - let’s think of three explanations for the existence, not the size, or stratification. Stratification is really important. Also, depending on who you read, stratification is both awful and glorious. Quoting Kant:

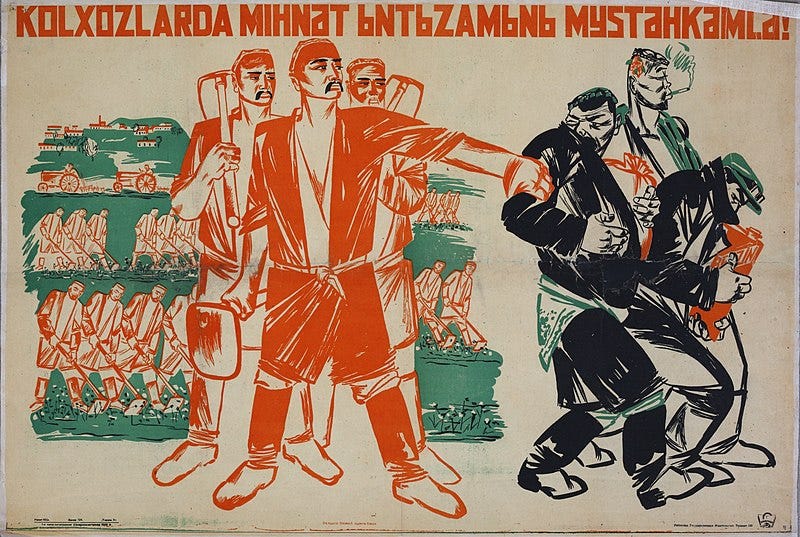

The Soviets, via Rousseau, are Wrong

RD begins with a sweeping summary of a longstanding debate. On the one side is Aristotle, who argues that people are fundamentally unequal in their social rank. By the 18th century, this argument gets firmly rejected.

On the other is Rousseau and friends who argue that, actually, humans are equal. The stratification of social rank doesn’t exist “in a state of nature.” Rather, our society, mainly private property, creates human stratification.

Or, that is, private property sows the seeds of the kinds of stratification we see today. This argument leaves equality in some original state of nature as a given.

Then, the Soviet Union comes along and unequivocally shows that, no, private property alone is not the wellspring of all the stratification that we see.

So we have the Soviets. Their answer for why stratification exists follows this Rousseau tradition - eliminate private property, eliminate stratification. Ownership of property is the original sin from which stratification flows. The project of the Soviet Union was to rip out the stratification generation mechanism to inevitably produce inequality.

Of course, the Soviet Union was a disaster, one stuffed full of other kinds of stratification. So, no, private property is not where we find the origin of stratification.

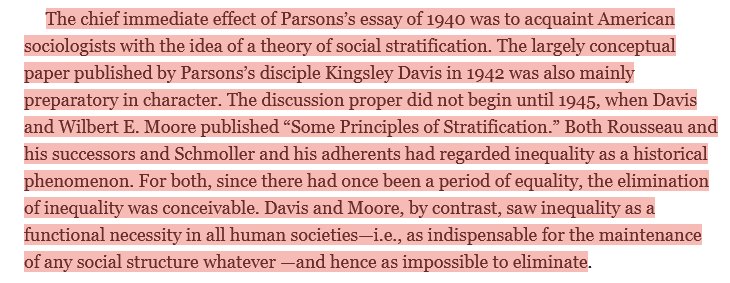

The Durkheim-ians are close, but off

Then we have folks like Durkheim and Simmel. They argue that the division of labor in a complex industrial society produces stratification. RD says this is wrong too. There are positions that are seen as functionally equivalent. And division of labor itself is more of an outcome of stratification, not necessarily the cause.

Kind of arguing that division of labor is the runny nose, not the virus. Se we still don’t have a satisfying answer.

The Functionalists are wrong

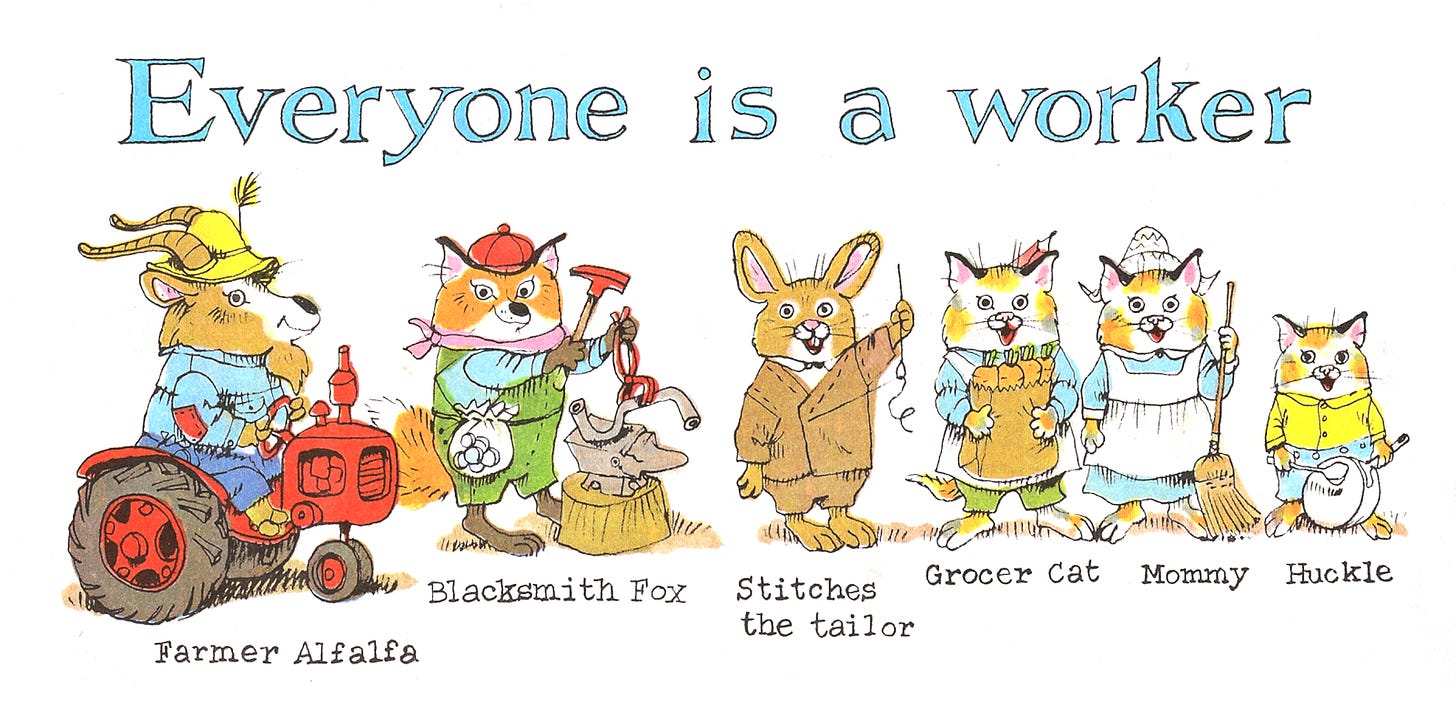

Then there are the functionalists, who see the world like a Richard Scarry book:

Everyone serves a role in society, and people are sorted based on their productive contribution.

That is, stratification exists because it is functional.

Stratification is the circulatory system that gets everything sorted and working.

Functionalists weren’t around for very long until they faced some very serious pushback. The theory was shown to be pretty darned weak. And not long after that functionalists were deeply hated in sociology. They’re now mostly a punching bag held up in graduate seminars.

Yet RD says: even the critics of functionalism only get the debate half right. This debate sits in a world of actually existing stratification, thinking about its function or lack of an obvious function. Where it comes from, well, we don’t get a satisfying answer in this theory or from the theory’s critics.

So the big theories, and their explanations - private property, the division of labor, and functionality, don’t get us to stratification origins. RD thinks he has an answer:

Social Norms are Necessary, Social Norms make Stratification

Human society is regulated by norms

Here’s an example RD gives of gossip in a neighborhood:

Here’s an example of social norm enforcement by Jerry Seinfeld:

We need norms. We enforce norms. We reward folks who follow societal norms and punish those who violate societal norms. Thus, we have stratification. Norm enforcement may seem to be individual-ish thing - people enforcing expectations and people receiving punishment, not a societal-level thing. But norms let us get back to the social origin of stratification:

Norms have no capital-t truth to them. They are simply ways to enforce social order. Thus, there’s always going to be some kind of discrimination, even very modest, that exists within society.

Certain norms make certain social positions privileged and deviant, and makes the ability to keep up with current norms easier or harder. For example:

How norms make stratification

Here we have the money paragraph, where RD explains how norms create stratification.

There is inequality because there is law (law broadly conceived: norms, rewards, and sanctions). If there is law, which there must be in any society, there will be stratification.

This is true even in societies where individuals are equal in front of the law - where laws are designed for universal application. RD says that such situations still have norms as the fundamental pillar of stratification. That is because even if we are all equal before the law (or the norm), we are unequal after it.

We are punished and rewarded for deviating from / following the law / the norms. Rewards can simply be a lack of punishment!

There is no escaping it. You cannot opt out - societies cannot opt out. Societies cannot exist without some form of normative coercion, no matter how weak. When we live in a society, we live in a moral community, no matter how weak such moral coordination may be. A moral community is necessarily founded upon norms of behavior and belief, norms which are to be enforced (norms unenforced are not norms and thus do not cohere a group of people together into a society). Norm enforcement necessarily produced stratification.

So moral communities, a non-negotiable pillar of a group of people being a society, requires a bundle of norms to cohere that people together. Norms necessarily require enforcement, or they would not be norms. Enforcement necessarily requires people to get rewards and or punishment following norm enforcement. Stratification follows from the enforcement of norms:

When we think of stratification this way, power structures precede stratification. We have the power center which has its norms cohere society and whose norms are enforced. Power does not follow after stratification.

RD says to look skeptically at anthropologists who claim to have found flat, equal societies, which lack systems of authority and stratification.

Human society needs social norms, and needs norm enforcement, and thus needs stratification. To ignore this is to create disaster

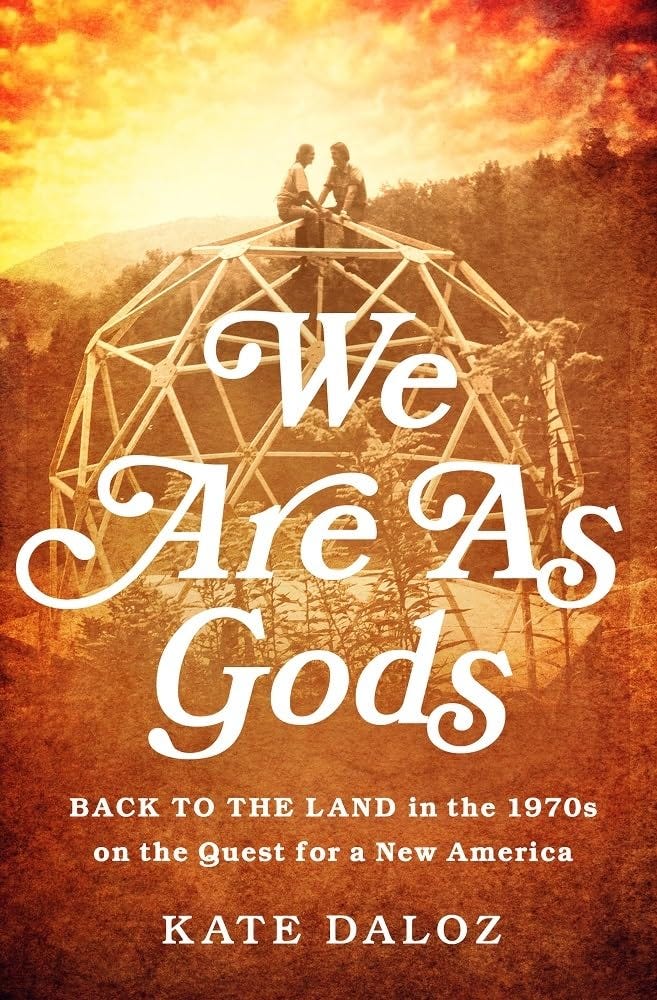

We can see this in the Soviet Union’s failed political experiment. We can also see it in the failed commune movement from the 1970s. I highly recommend Daloz’s extraordinary We Are As Gods: Back to the Land in the 1970s on the Quest for a New America

Oh boy - RD makes a big swing.

Norms. Sanctions. Power.

Important enough to put it in Heading 2 size. From these three does stratification flow.

Not everyone’s norms get to cohere society. When we talk about norms, we’re really talking about ruling norms.

Ruling norms, huh? Well, that explains why the functionalists are wrong. They don’t understand that the thing they’re trying to explain is the operation of the “ruling norms,” under which people do not happily bend their knee, or do so without any pain and friction.

Norm enforcement also implies rank enforcement. The functionalists are wrong. Folks low on the totem pole don’t live there happily. And they don’t live there for the pure creation of a functional society. So fights over norms and norm enforcement can create new social ranks and new manifestations of stratification.

Thus we are never at the end of history. We’re in the constant fight over norms and norm enforcement, which relate fundamentally to power, which can create new outcomes of stratification across social ranks. Stratification sows the seeds of social change, big or small, that occurs through the change of the dominant system of social norms, which will reshape the system of social rankings, privileges, and discrimination that people live within. This is a constant churn of change, reorder, updating, conflict, struggle, contestation. We’ll never enter into the utopian world of the Star Trek federation.

So we get back to Kant.

The power and domination is the bad. The constantly replenishing source of tension, creativity, and drive is the good.

This argument reminds me of the 2022 book review winner at astralstarcodex, written by Eric Hoel (who has a great substack, the Intrinsic Perspective)

Hoel’s reinterpretation of The Dawn of Everything: what we’re actually seeing is a massive fragmentation of social power across premodern societies. That sounds exactly like RD’s view of normative enforcement of moral communities necessarily producing stratification.

How I got here

I’m a little embarrassed to tell you how I ended up at this great essay. There’s an extremely weird and interesting couple who writes a book review blog, Mr. and Mrs. Psmith. They would be hill barbarians in a different age. In this one, they seem to be a pseudo-off-the-grid libertarian traditionalist family. Anyways, a few months ago they reviewed a book called Sick Societies:

The review was very interesting and aligned with my amateur interest in societies that collapse. So I decided to read the book (the book was not quite as spicy as the review made it seem - but it was an interesting book nonetheless). Edgerton referenced Dahrendorf’s idea from this essay in his book, and while I had heard of RD, I hadn’t heard of his argument regarding stratification and law. So I hunted down RD’s book of essays and read it. And it was great! That’s all to say: there are wonderful winding paths to new arguments if you follow the citation trail of weirdos with whom you share almost nothing in common, in terms of life circumstances or epistemological perspective.