Monks Die Equally

I really, really love this study. This is the kind of thing that got me into sociology. Schmitz et al. test a core theory of medical sociology: fundamental cause theory.

FCT says: socioeconomic status is a big cause of health and mortality outcomes. But the reason for this will shift over time through a variety of flexible and changing pathways and connections. Folks in higher socioeconomic strata can deploy their resources - material, knowledge, connections, capacity, etc. - to improve their health in a wide variety of ways.

Well, if that’s the case, how do you test FCT? Schmitz et al. notice one way that was lifted out as a challenge by FCT’s original developers:

If you find folks in different socioeconomic strata who are highly constrained in their ability to deploy the variety of resources that socioeconomic status provides to improve health, you should see reduced health disparities across socioeconomic status groups.

So let’s take a look at the monks!

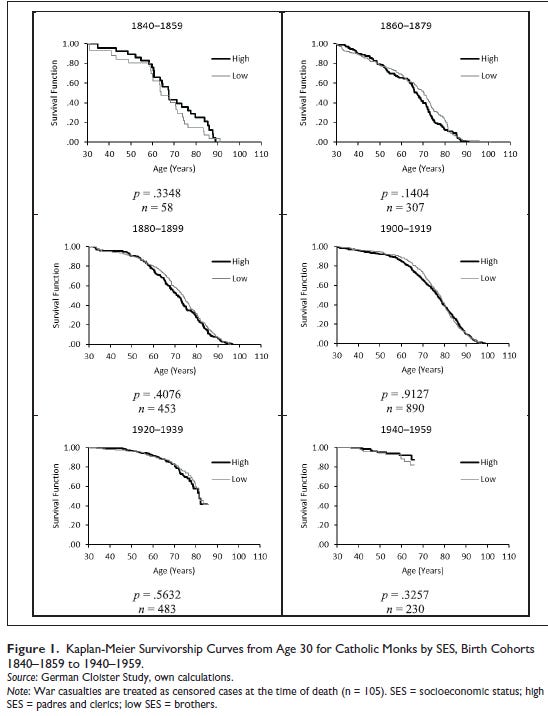

Schmitz et al. find a great data source of Catholic monks in Germany, born in the mid 1840s through the 1950s:

There are two rough socioeconomic groups: padres and brothers. The team ends up with about 2,400 monks and track their mortality timing. And the monastic life should level inequalities across groups and reduce class-based stressors:

We get this glorious finding:

We’re looking at survival curves: e.g. the percentage of monks, separated by padres and brothers, across decades, who lived to certain ages. We see that the two lines are pretty darned similar in every little panel. So class differences did not result in monastic mortality differences.

This translates into support for fundamental cause theory:

Is there a robust sociology of monks and nuns that I am not aware of!?

Why the lack of a gap? Schmitz et al. speculate a couple of mechanisms: behavioral spillovers of health behaviors from padres to brothers, a lack of stratified working conditions across brothers and padres, more - and more equal - social connectedness across brothers and padres, reduced exposure to killers of lower SES strata like murder, poisoning, suicide.

But the big point: a social group where socioeconomic resources are leveled result in the equalization of mortality across socioeconomic groups. SO. COOL.

OK Boomers, not-OK Millennials

Hui Zheng is one of those academics who produces extraordinary work but never really ends up in the New Yorker or the New York Times or the Ezra Klein show or Twitter. Which makes me skeptical of the pipeline between higher education and national public prominence. Because Zheng is a great research who, in a system of quality-based selection, would be a household name. But that’s just one random sociologist’s opinion.

Anyways. Zheng et al. conduct a very interesting study that tracks the decline in health and mortality from the Baby Boomer to the Millennial cohorts. They use a high quality panel study - the Panel Study of Income Dynamics, and focus on a wide range of factors that trade off, some improving health and mortality, some worsening it, that ultimately result in the weird worsened health outcomes among America’s greatest generation - the Millennials (I’m a Millennial, but this surely is an objective statement, not an opinion).

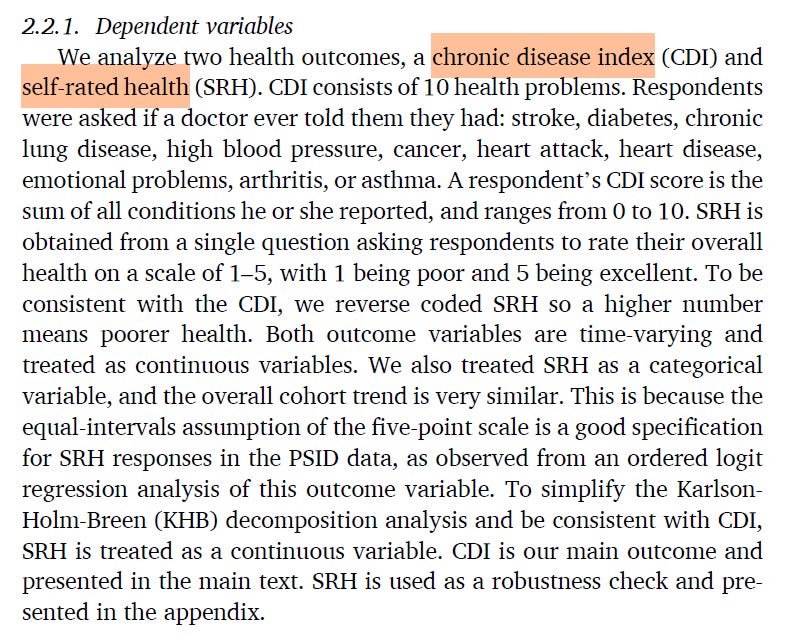

Their outcomes: a chronic disease index and self rated health

They look across birth cohorts - early and late Baby Boomers, early and late Gen X, and Millennials. They look at early life contributors to health:

And adulthood factors:

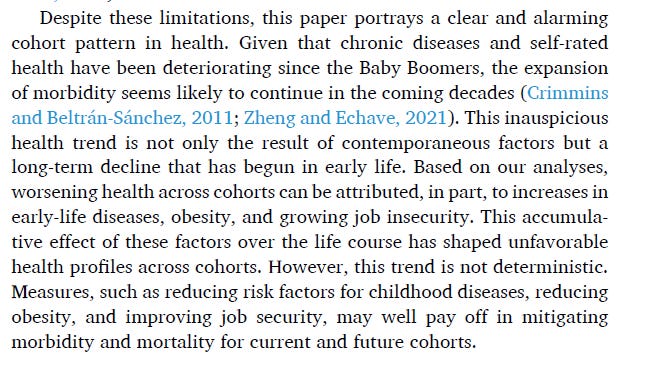

Overall, there are offsetting factors that have resulted in worsening health and mortality among recent birth cohorts:

They show that the big contributors to intercohort rise in chronic disease: early life disease, obesity, and job tenure (e.g. increase in economic insecurity).

A fairly large chunk of the intercohort rise can be attributed to these factors.

Their big conclusion:

Poverty Kills

Speaking of Zheng, he had a great article with Dave Brady and Ulrich Kohler that showed that, well, poverty is bad for things like life and death.

They again use the Panel Study of Income Dynamics. They measure relative poverty, or falling at or below 1/2 the year-specific median income. They measure income after all taxes and transfers are taken into account, and they adjust for household size. They also measure cumulative exposure to poverty - living in 20 years of poverty is probably different than having spent a single year poor.

They find what should be obvious, but is nevertheless very important. Poverty reduces years lived.

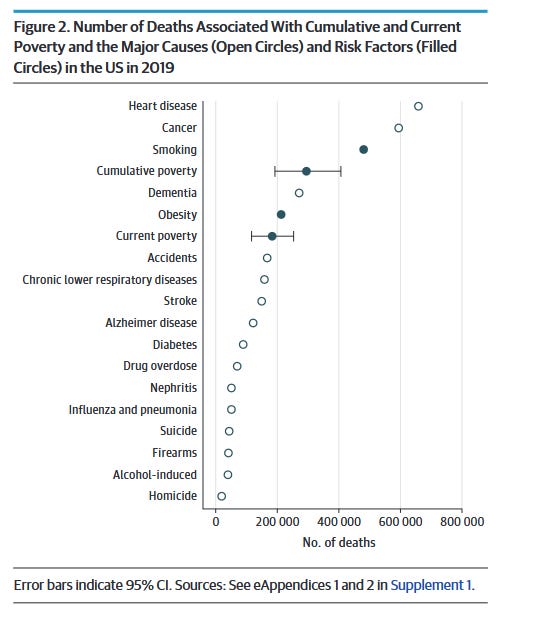

It’s not just that poverty reduces life expectancy. It’s that it sits with some of the bigger players of life expectancy.

Cumulative poverty was only outpaced by heart disease, cancer, and smoking in terms of the magnitude of death rate.

These findings aren’t cherry picked. They run a whole bunch of robustness check models, and the main findings sit in the middle of the distribution of effect sizes:

Simply put, it’s extremely risky for one’s health to be poor in the United States. Poverty reduction programs would also probably be health improvement programs. I love the elegance and simplicity of this paper.

Job Insecurity Makes Grey Divorce

I’m a big fan of Rachel Donnelly. She does really cool work at intersection of job insecurity and health.1

Donnelly’s study is straightforward and elegant. She focuses on “gray divorce,” or divorce among individuals aged 50. The general idea: such gray divorce has grown in frequency and importance, older adulthood is a time where lots of people are still working, it’s a time where many folks are transitioning to the relatively insecure state of retirement, and economic insecurity likely produces material (e.g. lower income), volatility (e.g. there’s greater uncertainty), and psychological (e.g. you’re stressed and sad!) problems for folks that increase the likelihood of relationship outcomes like divorce.

Donnelly uses a high quality dataset of older adults: the Health and Retirement Study, and tracks heterosexual couples between 1998 and 2020.

The key outcome: divorce. She follows couples over time and measures whether folks’ marriage survives over the 22 years of the study with or without a divorce.

Donnelly’s main predictors: labor market status and economic insecurity. The latter is a bundle of several characteristics:

Basically, Donnelly differentiates folks not working, folks working and not insecure (based on perceived insecurity and short job tenure), and folks working who are insecure.

The big finding:

Some factors - like disability, labor force participation, unemployment, have big effects increasing the risk of divorce. Husband’s economic insecurity increases the risk of divorce. Wives, not so much.

The big conclusion:

And this is, if anything, probably an understatement of the effect of insecurity on marital stability. Donnelly notes that her data selects on people whose marriage lasted until older adulthood. Thus, younger adults whose relationships were disrupted by insecurity aren’t measured. So we’re looking at a fairly extreme case of insecurity producing relationship instability.

Some general thoughts

There is a very, very subtle theme to these studies. I’m not sure if you picked up on them. But it’s that socioeconomic inequality and negative labor market conditions tend to screw up health and wellbeing. Removing SES-style disparities reduces brother-padre mortality. Poverty increases mortality. Labor market insecurity reduces health. And labor market insecurity increases divorce.

The obvious idea is that improving labor market conditions and reducing socioeconomic inequalities should have a straightforward consequence of improving health.

We could presumably assess this claim through cross-national comparative research - how do trends in post-fisc inequality, or post-fisc economic positions among the bottom 20% translate into subsequent changes in health? We could also look at many of the changes that have occurred since around 2012 or so. This has been an era in the US of tight labor markets and large corporations making pretty aggressive efforts to increase firm-level minimum wages. You would think these two factors would produce better health, all else being equal (And if you don’t find these associations, then the question becomes: what the heck is going on!?).

Lane Kenworthy has a book that is coming out that will argue that inequality doesn’t really produce any meaningful social outcomes. I’m sure that he’ll take a look at health as a major chapter. I will read that very closely to think about how to interpret the studies discussed above.

Despite using it here, I kind of hate metaphors like "at the intersection of X and Y,” which I primarily associate with desperate attempts to grab status. My perennial 17-year old brain always wants to make snarky modification, like, “This research sits within the roundabout of insecurity and health.” But it’s such a niche and minor annoyance that there is never really an appropriate place to express it. Perhaps this footnote is where it will live and die.