This Monday’s we’re going to take a look at some articles that focus on gender inequality.

Awkward Introductions Reveal Gendered Cultures

Let’s say that you suspect that a negative and gendered culture undermines things like women’s hiring, retention, and advancement in STEM work and fields. How could you study the effect, or even the presence, of such a culture, especially in an era where most folks know how to refrain from the most obviously sexist statements and behaviors?

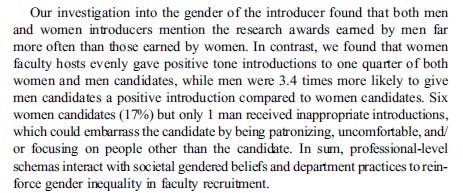

Blair-Loy and colleagues conduct one of the more ingenious studies that I’ve read in recent years. They read or watch nearly 200 introductory statements to job talks in two engineering departments at research intensive universities. These introductory statements give a bit of an assessment of the candidate, and sets the frame of what is relevant to focus on in their research talk.

Long story short - women face a much higher rate of inappropriate and irrelevant comments, and men’s achievements are played up way more.

They dive deep into previous literature that shows a gendered pattern of evaluation in STEM fields.

Professional culture matters.

Scientific excellence, particularly in STEM fields, have a deeply male-centered logic

They collect data from a large set of recorded introductions to job talks. And the researchers code the language to identify neutral, positive, irrelevant, negative, and other instances.

An example of a neutral introduction:

Positive introductions:

Irrelevant introductions:

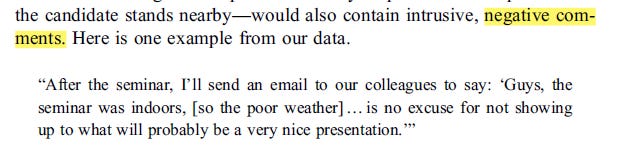

Negative introductions:

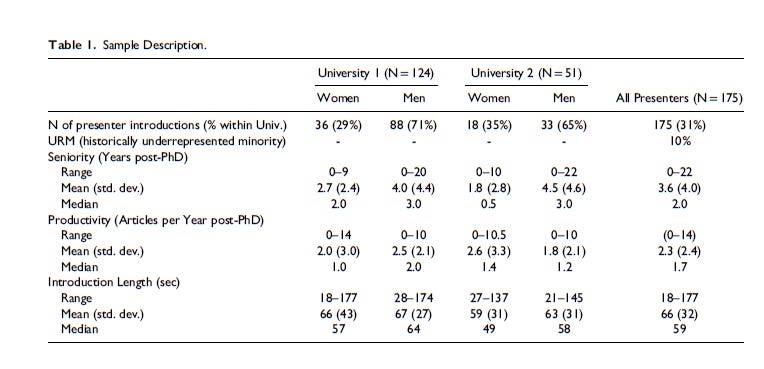

About 35% of the job candidates were women. There wasn’t a major difference in research productivity between men and women.

Men’s awards were mentioned more frequently than women’s in the introductions.

Positive tones were used more frequently for men than women in the introductions (look at the percentages in the far right of the table - 39% of men had positive tone introductions, 17% of women).

Inappropriate / irrelevant comments were used more frequently for women than men (for 32% of women, and 16% of men for irrelevant content, 11% for women and 1% for men with inappropriate content).

There’s just a major difference in how a very homogenous sample was described, based on gender.

Culture matters, and there seems to be a real, measurable culture in these engineering programs privileging men over women. If you’re interested in this, Blair-Loy has been on a real streak in recent years studying the many mechanisms that result in gender inequality in STEM places.

Gender, wellbeing, and norms in the medical field

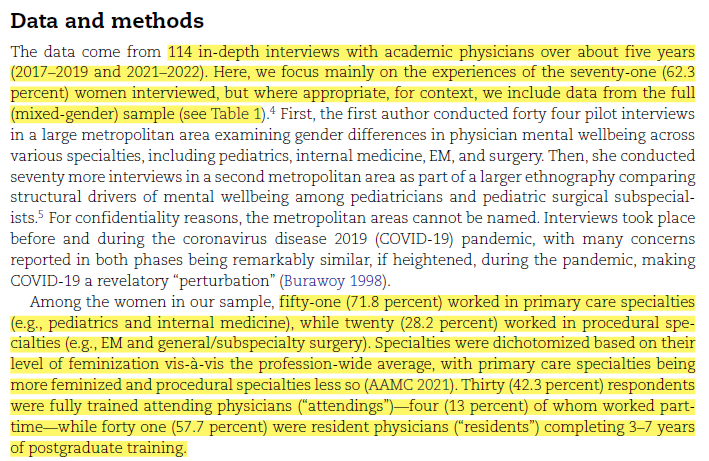

Tania Jenkins is an incredible medical sociologist. Her recent study looks at the link between occupational feminization (e.g. the percent of folks in an occupation that are women), work culture, and mental health among healthcare workers.

Women are increasingly entering into the physician profession, with differential rates of female occupational attainment. Jenkins uses these trends to ask the question - how do the expectations and norms in a field traditionally male coded and differentially becoming more female affect women’s mental health?

She conducted a five year study, interviewing over 100 academic physicians. In this project, she focuses on physicians in a field that is now primarily female - primary care - and that is primarily male - procedural specialties.

Women had higher rates of burnout and lower rates of mental health compared to men in these fields.

A range of norms, expectations, and workplace habits retained a more male-coded work culture, which ended up causing quite a bit of strain and distress among female physicians.

Physicians were expected to be fully tethered to work. They were expected to be untethered from other things like family obligations.

Even among primary care, which is predominantly female, these expectations of untethered-ness remained, which if anything created greater frustration among female physicians.

Sometimes this tethered-ness was formally written into policies - such as extremely long shifts for new physicians. Even when those policies weakened, expectations remained.

Physicians were expected to be “superhuman.”

These expectations often translated into isolationism and stigmatizing the idea of things like self-care and help seeking.

Yet it seems that this norm, while not as strongly held among primary care physicians, if anything was a greater stressor in this field.

Physicians are expected to be stoic.

There’s really no winning for women when it comes to adapting, or not, to a more masculine-standard of emotionality within the professions.

Overall, a primary masculine culture was retained in both specialties, which created stress and undercut wellbeing among female physicians.

Two big things. Simple compositional change - e.g. women going from 20% to 45% of occupation holders - don’t change cultural and institutional norms.

Second, proportional representation itself does not guarantee a change in culture, institutions, organizational logics.

Changing Gender Compositions of Carework Over the Century

Gonalons-Pons is one of the best demographers out there, in my opinion. This interesting study looks at long term changes in gender differences in care work.

They begin with a basic observation - lots of folks are saying that there’s been this big shift to paid care work. And they ask the fundamental question, “…has there?”

They use Time Use data (e.g. a large sample of folks are given time diaries and record detailed information about what they do throughout a random week) and administrative employment data to get at this question.

I don’t totally understand how this is a demographic framework, rather than just a high quality quantitative social science framework. But perhaps one must say this to publish in a journal titled Demography!!

The authors claim that there have been big changes since the early 1960s: the defamiliazation of care work (e.g. outsourcing to a retirement home / daycare), the rising need to care for older adults, and declining levels of gender and racial inequality in care work. So let’s break apart these dimensions and look at care work trends over time.

Here’s what I love about their paper - they want to look at the combination of all time spent in care work in a particular year. So they need to mix paid and unpaid care work (e.g. caring for you toddler at home, and a daycare worker caring for a toddler at a daycare).

They say - let’s think of all the total hours in a year that people devote to care work.

This equation basically says - add up all the hours X caregiver counts in a particular year, differentiated by race and gender.

They grab unpaid care work from the time use data. And they grab paid care work data from the Current Population Survey. Then they smash them together to get a toal number of yearly hours of care work.

… grabbing paid and unpaid care work from each of the data sets, then smashing them together into total hours in care work!

You can then decompose the amount of hours in any particular year going to care work from paid and unpaid sources, men and women, and folks by different racial groups.

The main results.

Lots of interesting things happening. First, looking at the left panel, total time in care work has gone up, with the main driver unpaid childcare and, to a lesser extent, paid childcare and unpaid adult care:

Looking at the right panel, you can see that the relative shares have shifted around a bit. But somewhat surprisingly, the relative share of paid versus unpaid care has stayed relatively stable over time. Look at the middle “total” columns, which show the proportion of care work provided by paid caregivers.

The authors also note that the right-most column suggests a rising proportion of unpaid care work being devoted to adults, rather than children:

They next look at gender contributions:

A lot going on here - the big finding is that there has been a real shift in men doing a larger proportion of care work over time.

For racial groups:

Somewhat contradictory evidence:

The overall conclusions:

Very real and important changes over time, but not as much evidence of massive de-familiazation.

I love this study, and I hope they do more work to follow it up. For example, let’s say that in 1960 five people spent one hour apiece caring for their children. Then in 2010, one daycare worker spent one hour caring for those five children all at the same time. Is that a stable amount of care work over time or a decline? If it’s a decline, then presumably we could sedate 10,000 elderly people and have them cared for by one person on their phone, rather than having 10,000 individuals provide care, and observe a decline in care work. But we would be seeing a stable cared-for hours worked, a decline in caring-for hours worked, and a decline in quality of care. I would have never thought of these issues without this fascinating study.

Gender (and Racial and Educational) Gaps in Healthcare Professional Careers

Which Health Professional School Graduates (HPGs) get matched to healthcare jobs? And how does this matching vary across gender, race, and place of origin? Those are the questions Schut sets out to address. Healthcare professional work is rapidly diversifying, and many folks are hoping to immigrate to the US to train as HPGs and land healthcare jobs. Yet healthcare work has a variety of closure mechanisms making this matching hard, and there are the usual suspects of differential treatment along race, gender, and nativity status.

Schut uses an interesting dataset, the National Survey of College Graduates, to track folks who are matched into particular healthcare professions.

The key variables:

The main results are in these figures

There are surprisingly large gaps in the probability among US-educated HPGs - around 0.13 and 0.06 - between White men and Black and Asian men. Meanwhile, there aren’t huge racial gaps among US-educated women, but notice the much lower starting point of the probability of healthcare employment.

Finally, notice the massive nativity gaps that end up with foreign-educated women having the lowest probability of healthcare employment. And while you can’t really see it too well there are pretty large gender gaps in there, right? So even among a homogenous sample of folks who got healthcare degrees, we see a gendered mismatch in ultimately ending up in healthcare work. This article doesn’t address the mechanisms of why, but important descriptive findings nevertheless.

The big conclusion:

Tax Policies Make Gender Inequality in High Income Couples

A clever study that focuses on a weird tax quirt - a threshold for payroll tax contributions - that ends up making gender inequality within higher earnings couples.

Thus, their argument:

The US has a funky payroll tax system that, combined with its high inequality and gendered labor market, can produce some funky results:

We see some odd bumps within an overall progressive tax system.

There is space in this funky tax system where it might make economic sense to take one’s foot of the employment gas pedal. And, given the gendered norms of work and homecare, we’d expect couples to default that downscaling of employment to women.

The authors use a high quality panel dataset, the Panel Study of Income Dynamics, and tracks couples between 1977 and 2017.

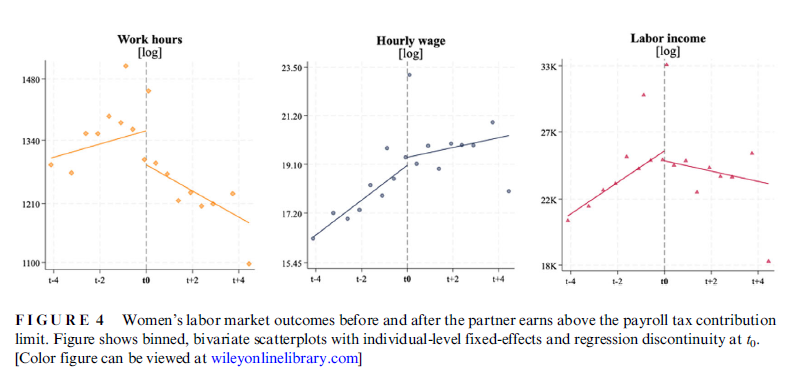

Their main outcome - women’s work hours, wages, and gross income. The main treatment is partner’s payroll tax status.

They use a set of regression techniques - fixed effects with individual slopes - to examines changing earnings and work hours trajectories within women over time.

A big descriptive gap in women’s earnings among those ever and never “treated” by this funky payroll tax threshold.

We thus see lower incomes among women whose partner hits this threshold, primarily occurring through lower work hours.

The decline occurs gradually over time after womens’ partners enter the “treated” category.

The big conclusion:

My read - if there’s an aggregate incentive for couples to ask the question “why are we working this much if we’re not earning money,” then people will tend to take their foot of the gas on the aggregate. And the downshift will follow gendered norms of who should be a breadwinner.