One Great Read - Globalization and Union Decline

Roshan Pandian does it again! Globalization eats unions' lunch.

I’m such a big fan of Roshan Pandian’s work. We overlapped a bit during graduate school at Indiana (I was a few years ahead of him). He is producing extraordinary work on global inequality topics. You can see my last great read that focused on his work here:

One Great Read - Global Inequality

I’m going to spend a tad extra time on a great article published in one of sociology’s “top two” journals, The American Journal of Sociology. Roshan Pandian published an extraordinary paper on the change to global inequality in the 2000s. AJS articles are

Well, with Matthew Mahutga and Manjing Gao, Pandian’s done it again!

This article tackles a basic question: does global trade - particularly trade between less developed countries (LDCs) and rich democracies undermine unionization in rich democracies? There is a theoretical reason to expect that global trade will undercut unionization in rich democracies:

Think of the Bruce Springsteen songs in the 1980s, talking about factories packing up and moving out.

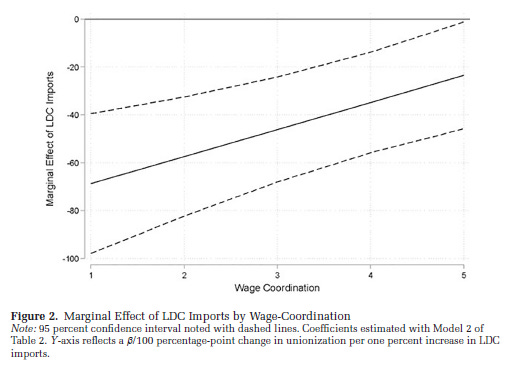

This article challenges an established finding in the literature - that globalization, particularly trade with less developed countries (LDCs) has had minimal influence on the broad phenomenon of labor union decline in rich democracies. Mahutga, Gao, and Pandian (MGP) say that the consensus of this minimal effect suffers from some theoretical, empirical, and measurement issues.

Global trade between rich democracies and LDCs has increasingly become incorporated into supply chains of profitable firms that are largely headquartered in rich democracies (think of supply chains that end up as squishmellows for sale in Walmart). The aggressive pursuit of low prices crunched suppliers in LDCs, which kind of fed into the argument of globalization reducing rich democracy unionization (firms pursuing low costs offshore).

More global value chains anchored in rich democracy firms / headquarters, the more that LDC trade should undermine unionization.

As I understand it: there are older-school arguments and theories about global trade that conceptualize firms in the United States (Plushie Inc) and firms in Bangladesh (Stuffy Inc). Both Plushie Inc and Stuffy Inc are in a competition making as many Squishmellows for as little cost as possible. And Stuffy Inc outcompetes the unionized and high labor cost Plushie Inc. However, what actually happens is that WalMart tells Stuffy Inc - make me an army of Squismellows. And if Stuffy Inc in Bangladesh won’t do it, we’ll simply take our talents to Squish Brothers Inc in Bhutan.

Lead firms in rich democracies, e.g. Walmart, have suppliers in LDCs over a barrel.

So Walmart crunches overseas suppliers, which subsequently enables crunching higher paid workers in rich democracies:

Everyone gets crunched by the lead firms, in their own way:

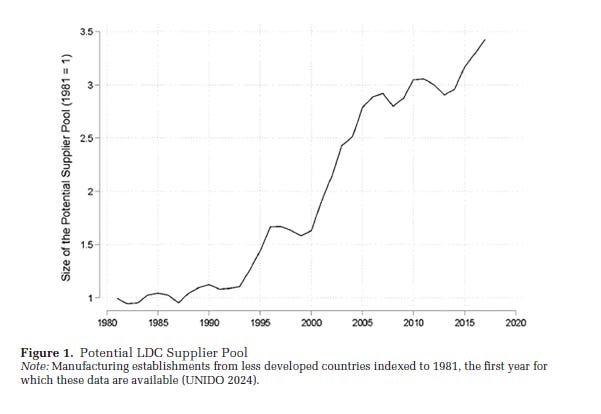

So we have lead firms increasingly able to play suppliers across LDCs against one another. We see a rise in the potential supplier pool in LDCs over time

This is a fairly fragmented system where the rise of potential suppliers doesn’t necessarily reduce the bargaining power of lead firms - it allows lead firms to pit suppliers against one another. And the concentration of lead firms (think the work of superstar firms, corporate consolidation that’s popped up in Economics the last decades) makes for fewer lead firms which the suppliers can bargain across. So … lots of cost crunch in LDCs, lowering cost and reducing the bargaining position of rich democracy unions. Oof!!

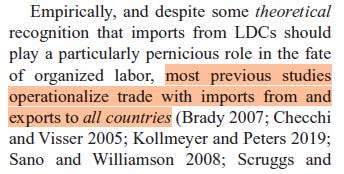

The measurement of global trade has been a bit off too:

MGP also assess the extent to which the link between LDC trade and unionization varies across institutional contexts - e.g. the sparse American context and the more protective and centralized Swedish context.

The dynamics described above aren’t captured by the traditional measure trade openness.

The authors also discuss the variation across counties with different labor market institutional arrangements - e.g. a more coordinated and centralized Nordic system versus a more fragmented and fancy free system like the US.

Empirics

MGP examine about 1,000 country years from the 1960s to late 2010s, focusing on 22 rich democracies:

The authors use two empirical tactics beyond standard two-way fixed effects models. They use a “double de-meaning” strategy to correct for interaction terms (e.g. allowing for the effect of globalization to vary across labor market institutional contexts)

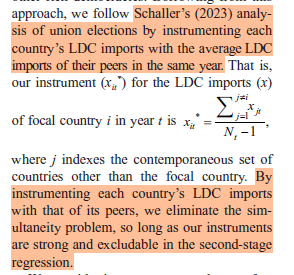

and they use an instrumental variable strategy to account for the endogeneity of globalization on unionization:

Their instrument: the peers of a country’s imports from LDCs:

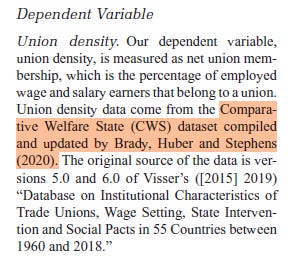

The main outcome: unionization.

The key independent variable: LDC import penetration

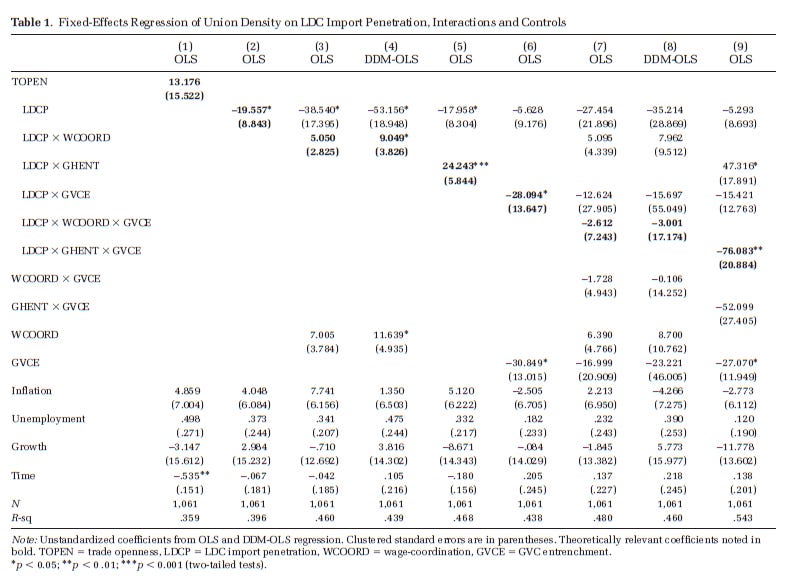

The results are sadly table-heavy, and so don’t make for the best blogging:

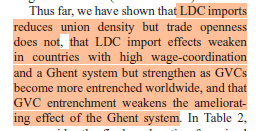

TOPEN is trade openness. It has no relationship with unionization. LDCP is trade with less developed countries. And it reduces unionization (see the negative value in column (2), and the * indicates an effect significantly different from zero)

The effect is stronger when they use their instrumental variable strategy to address concerns of endogeneity

Are we just seeing the most free-wheelin’ countries, like the US, driving these overall effects? Kind of, but not really

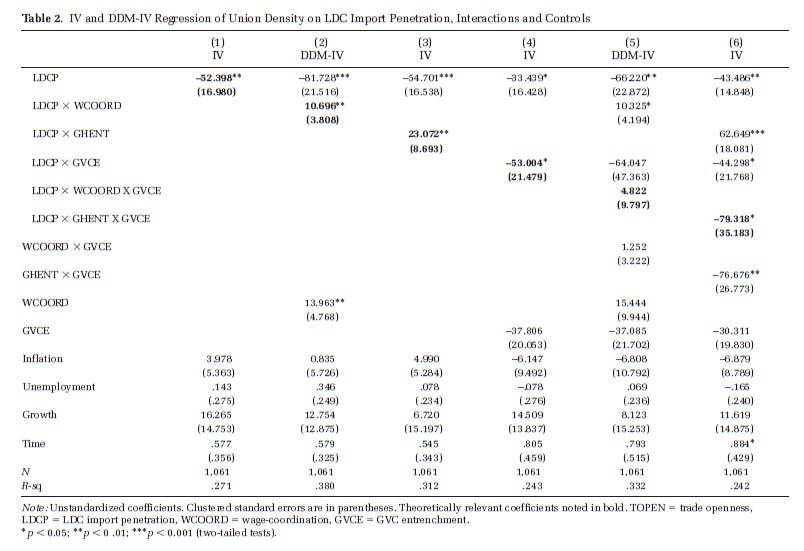

Wage coordination of 1 is a place like the US. Wage coordination of 5 is a place like Sweden. LDC imports dampen unionization everywhere, but the effects are largest in places like the US. Labor market institutions modify the overall association.

MGP run some counterfactuals to show the potential impact of globalization on unionization:

The red line is the unionization rate we observe. If all rich democracies had the most protective labor market institutions (gray solid line), unionization rates would have held steady over this period. If the effects of global value chains had been minimized over this period, we may have seen an increase in unionization. So the double damage of lead firms on crunching LDC suppliers and crunching unionized workers in rich democracies has been pretty massive.

This article pulls together a number of things that I love in modern sociological stratification research, and things that I frequently have a hard time studying myself:

This is a very firm-heavy study of union decline, even if the authors don’t directly study firms like Walmart. Their discussion of global value chains very much focuses on relationships between lead firms and their suppliers. Some of the most exciting and interesting sociological research is occurring at the firm level (think of work by Don Tomaskovic-Devey, Eunmi Mun, Nate Wilmers, Erin Kelly, recent work by Jake Rosenfeld, Dan Scheider’s team, and others). MGP take this line of research seriously and use it to unearth a key contributor to union decline.

Dang it, Roshan. He does such a great job of interrogating global inequality. It highlights my provincial tendencies to focus just on US surveys and datasets. This article, and work by Roshan Pandian and his coauthors, really force me to think about how US inequality trends are embedded in broader patterns of global inequality, globalized firms, and globalized processes of competition and worker power. You can’t really understand US union decline without understanding how WalMart is pitting squishmellow suppliers in Bangladesh against those in Bhutan.

A few stray thoughts:

I love the counterfactual. And I use counterfactuals in my own work. But I would take it with a grain of salt. Counterfactuals like the one I showed above state: assuming our model of the historical process holds, were we to vary one factor, we would observe the following trend. Of course, if we could hold GVC to a minimum value, we would require a different model of reality, because reality would be so different! Think of a counterfactual of the US labor market that models reality as it exists, but hold college educational attainment to its 1960s level. Well, if that were the case, we would need a different model of reality, because we would probably not have a tech sector AND a financial sector. Reality would be totally different! These counterfactuals are mostly a way of showing the magnitude of an effect (GVC had a big impact on declining unionization!) rather than showing an actual counterfactual reality that was possible.

The article doesn’t have much to say about China. Overall that’s fine, but my understanding of China’s long-term strategy is one of destabilizing the American hegemony across a variety of economic, political, social, and financial vectors (I’m reading Doshi’s fascinating book, The Long Game: China's Grand Strategy to Displace American Order, which probably brings this topic to the top of my mind). I suspect that China’s capacity to be pushed around by lead American firms has been time varying, and I suspect that China’s influence on rich democracy unionization, lead American firm influence, and the jockeying of LDC suppliers has been time-varying as well. This isn’t necessarily a critique of MGP’s main findings, but my gut sense is that the time period studied in MGP saw the emergence of another major global pillar that pushed in an alternative direction. It would be interesting to learn how China’s rise factored into the mechanisms at play.

The authors’ analyses stop prior to covid, and they do a great job discussing the potential changes we’ve seen in recent years. I’d love to see a replication of this exact study from 2018 - 2025! Is rich democracy labor sufficiently dead that LDC trade stops having an effect? Does the slowdown of globalization in recent years end the association? Does it still move forward, just at diminished magnitudes?

Sociology, for better or worse, tends to be a discipline that is a mile wide and an inch deep. My gut is that the folks mostly focusing on the topic of global value chains + global inequality are: M and G and P. I would really love for a massive research agenda organizing a bunch of different scholarly teams to emerge around this topic (well, I feel that way about a lot of topics in sociology that seem to be studied by just one or two people). I think the question of global trade, global value chains, and massive relational changes across global labor markets merits a heaping pile of multiple scholars’ attention. Sadly, that’s not sociology’s jam.