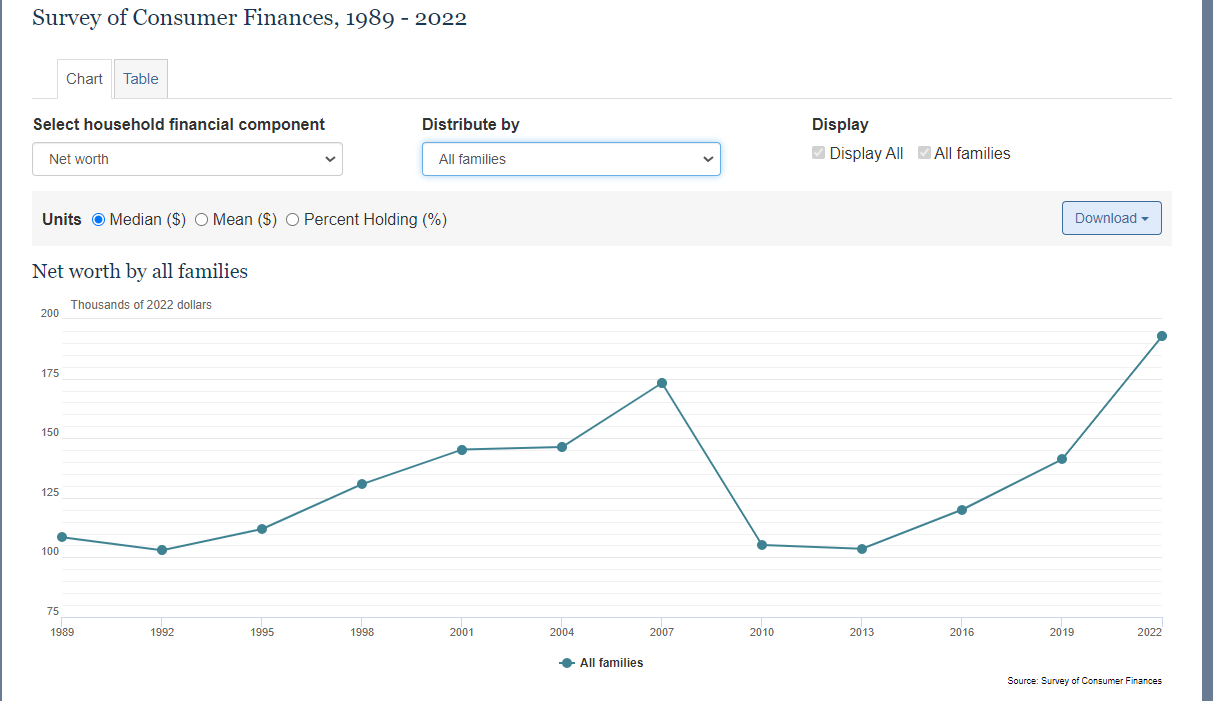

The Survey of Consumer Finances released its 2022 results recently. The top level descriptive statistics are just bonkers. It seems that the US had a massive wealth boom during the pandemic.

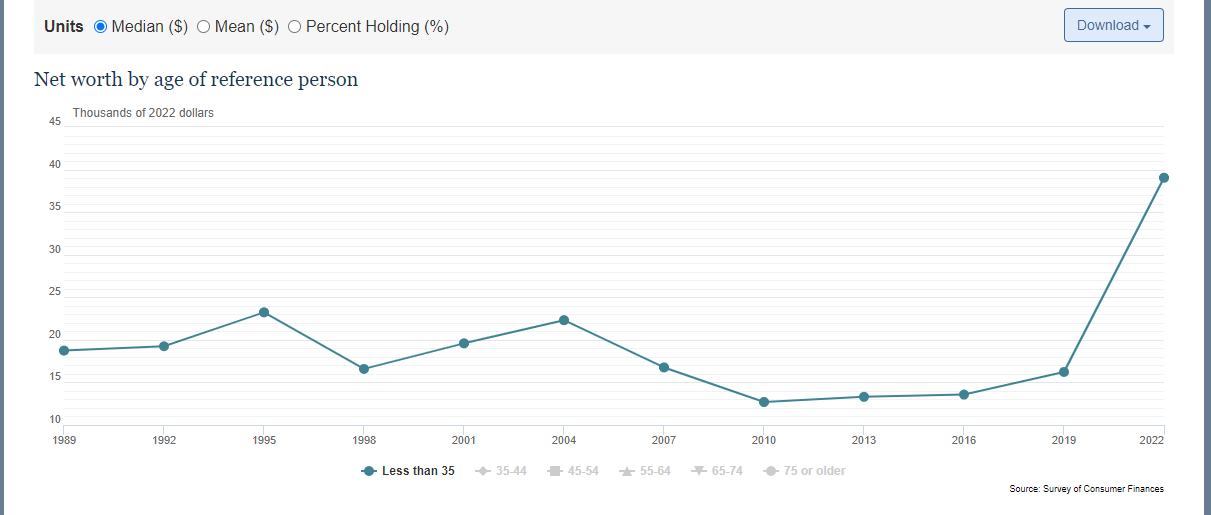

One of the major points of interest was the age-specific changes in wealth between 2019 and 2023.

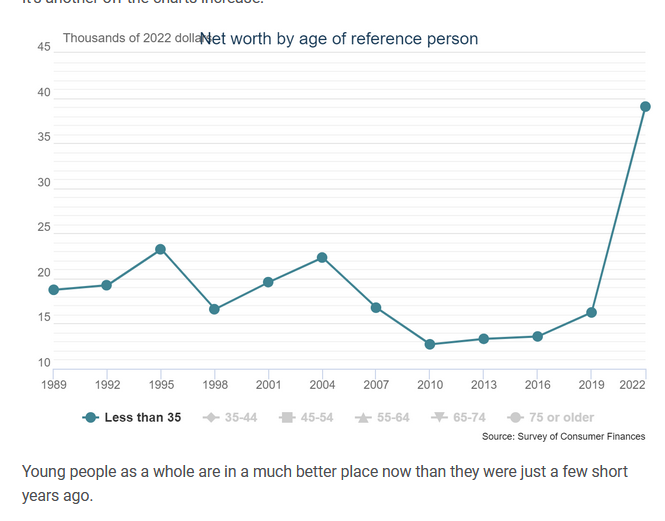

The median wealth of folks under 35 changed from $15,000 in 2019 to almost $40,000 in 2022. An unbelievable change, although we should compare it to the wealth levels of other age groups:

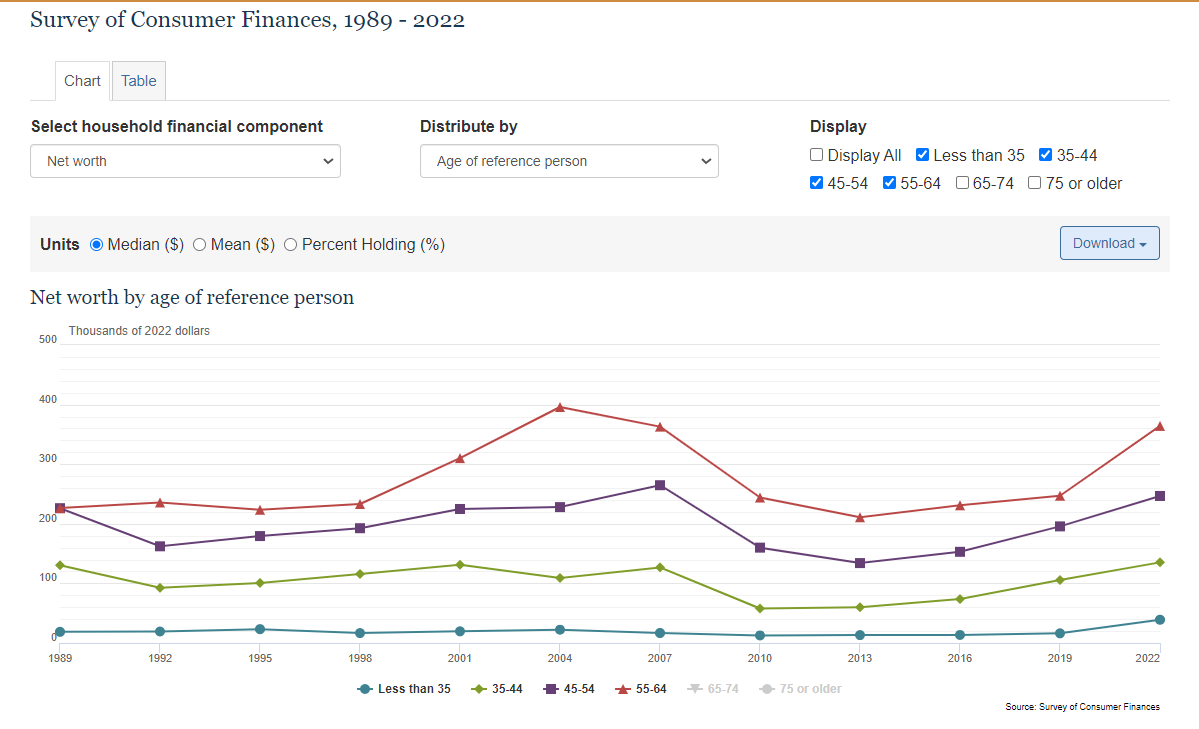

An unprecedented boost in wealth among younger Americans, but if I just eyeball these age-specific median wealth levels, the gap in medians between younger folks and older folks has remained roughly the same size as any of the other period, or has grown if we compare under 35’s to 45-54 and 55-64. Nevertheless, a big wealth boom that wasn’t just concentrated among the already wealthy (these are medians, not means. Mean wealth are super skewed by the very affluent).

The SCF results generated some interesting and contrasting interpretations. On the one hand is Ben Carlson, who runs an interesting blog on economics, wealth management, and financial information. He states:

Young people as a whole are in a much better place now than they were just a few short years ago.

Of course, this enormous increase in wealth had to be all housing-related, right?

The rise in housing prices certainly played a role here. Nationwide, housing prices were up 40% from 2019-2022.

But renters actually experienced an even bigger increase in their real net worth than homeowners. The gains were 43% and 34%, respectively.1

There are always going to be winners and losers in this system, but the financial position of American households improved substantially across the board.

He blames the media as the primary source of a general sour mood about economic conditions:

If it bleeds it leads. The higher the VIX the higher the clicks.

This is a real phenomenon.

The media spent the past 18-24 months bashing us over the head with recession predictions and talking about how bad inflation is. They don’t show counterprogramming when inflation falls or the economy improves.

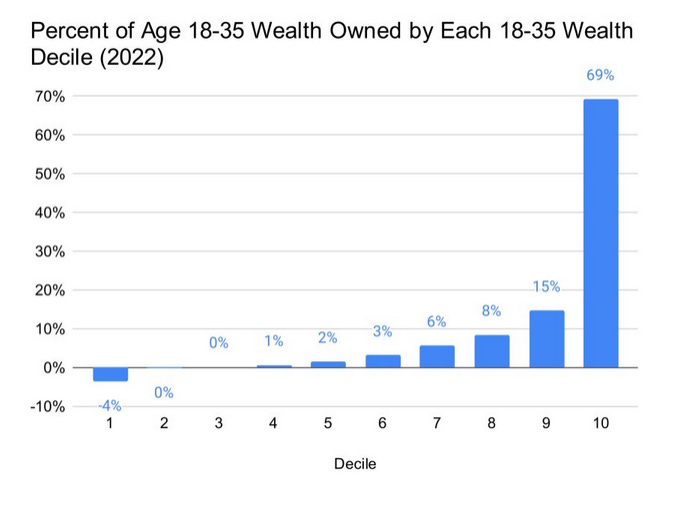

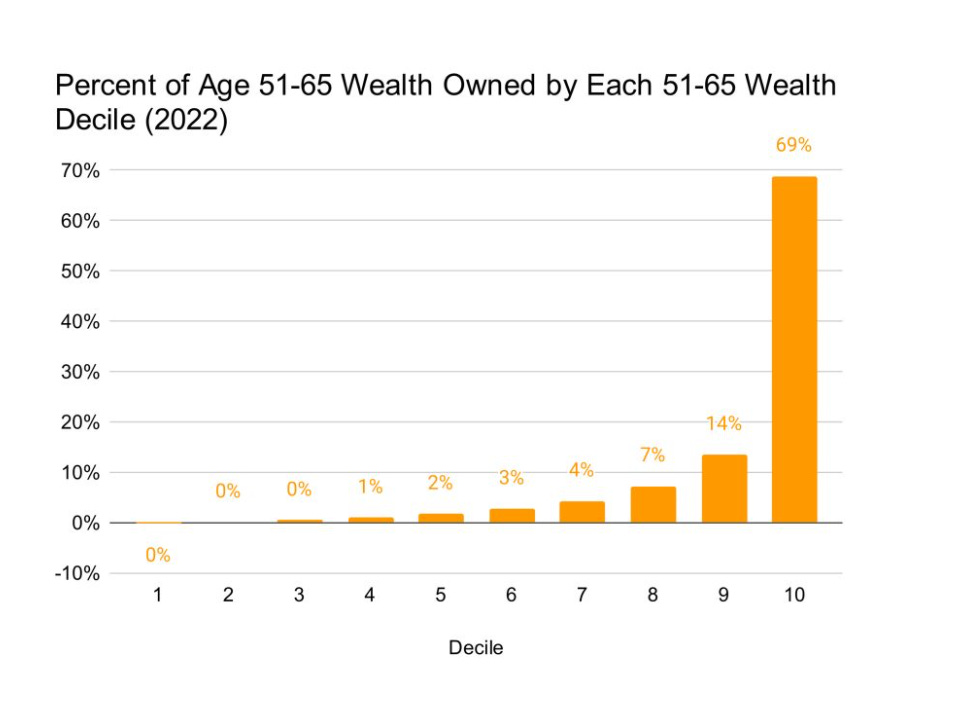

On the other hand is Matthew Bruenig, an insightful and grumpy thinker who cares deeply about egalitarian politics. He focuses on the persistent inequality levels of wealth across groups and categories:

The fact that we see the same wealth distribution over and over again no matter how we slice the data is a pretty solid indicator that this particular distributive skew is driven by the rules of our economic system, not a contingent issue with one group or another.

We see lots of wealth inequality across these age groups, inequalities that probably trump the over-time changes.

The way I reconcile these ideas is that they both discuss distributions. When we’re interested in complex things like wealth, the thing we’re interested in has many important dimensions and qualities: a center of the distribution, a spread of the distribution, a shape of the spread (is it bell shaped or a two-humped camel, for example), mean differences within the distribution across key subgroups, spreads around key subgroups, and political questions about which subgroups are worthy of measurement and consideration. All these change over time. And they have no requirement to change in a way that provides a researcher or commentator a simple, single summary comment.

Generational Wealth

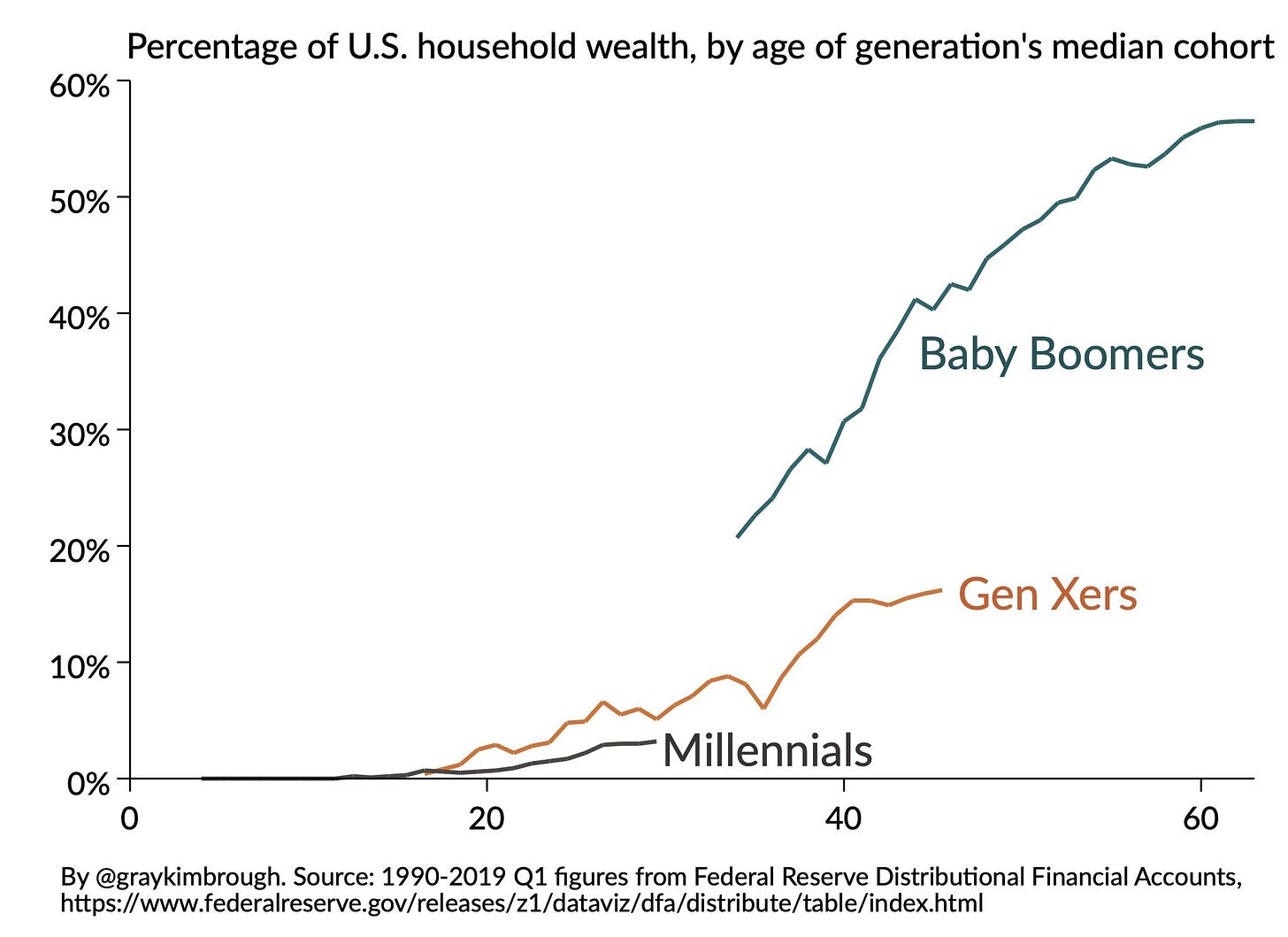

One of the most striking graphs that has circled academic-ish internet spaces shows the proportion of wealth held by different birth cohorts:

Some economists have pushed back against the striking generational differences.

Horpedahl makes the following critique:

…when Boomers were young they comprised a much larger share of the population. The original article makes an attempt to adjust for this, by calculating a few ratios towards the end of the article. However, there’s a much more straightforward way to adjust for this, which also nicely fits into a chart: put wealth in per capita terms!

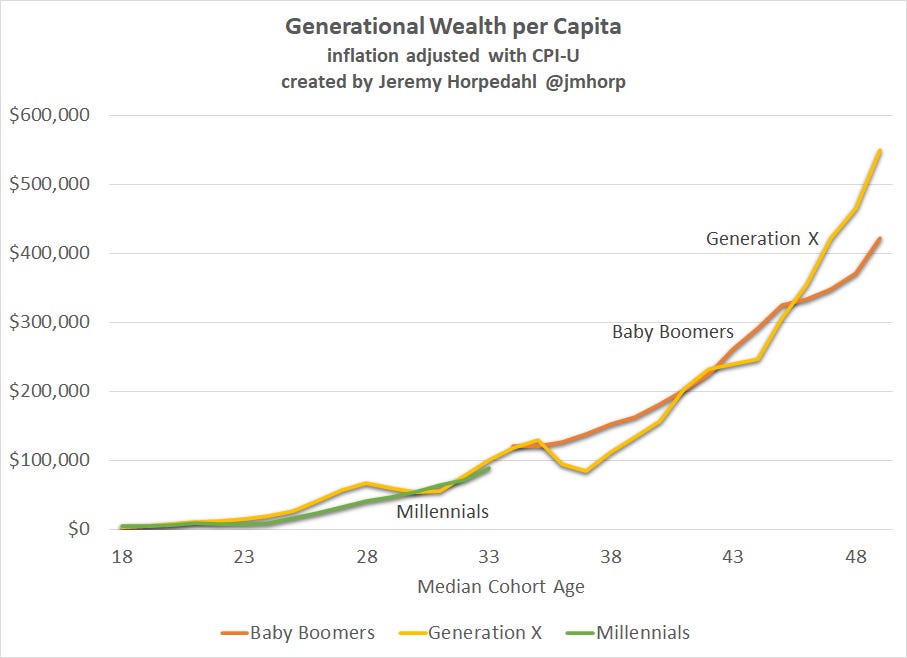

Adjusting for the group sizes he finds the following:

He changes the percent share that a particular age group holds in a particular year to the inflation-adjusted per capita wealth held by that age group in a particular year. When they do this, there are not major differences across cohorts. He then claims:

Looking at the exact same data (from the Fed Distributional Financial Accounts) from a different perspective gives us a much different picture of recent history. In this version, Gen X is now richer (30% richer!) than Boomers were at the same age (late 40s). Millennials don’t yet have a year of overlap with Boomers, but they are tracking Gen X almost exactly. There is no reason they won’t continue to track Gen X, and therefore exceed Boomers as well when they are in their late 40s (which will happen in about 2037 for Millennials).

He argues that these per capita measures are also improvements over shares

We might still wonder though: aren’t the shares of wealth still important? Isn’t it relevant that Millennials had a smaller share of wealth than Gen X at the same age, who in turn had a smaller share than Boomers? As presented in the chart, I would firmly say: no. It doesn’t matter that much that Millennials have a smaller share of wealth today than Boomers had in the 1980s. Inequality might matter for all kinds of reasons, but inequality matters at a point in time. It doesn’t matter in the sense the viral chart presents it.

These findings suggest that of the many qualities that define the Millennial birth cohort - fondly remembering media from our youth, sepia filters, taking photos of brunches- one can include incorrectly catastrophizing about economic doom. Similar arguments have been made about Millennial homeownership rates, which I looked at briefly in a previous post.

What if we account for the inequality part?

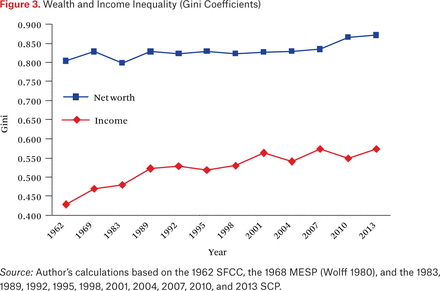

As I mentioned above, distributions are complex. Wealth is unusually unequal and skewed. An old article by Wolff nicely shows the extreme inequality for wealth compared to the much more modest inequality among income.

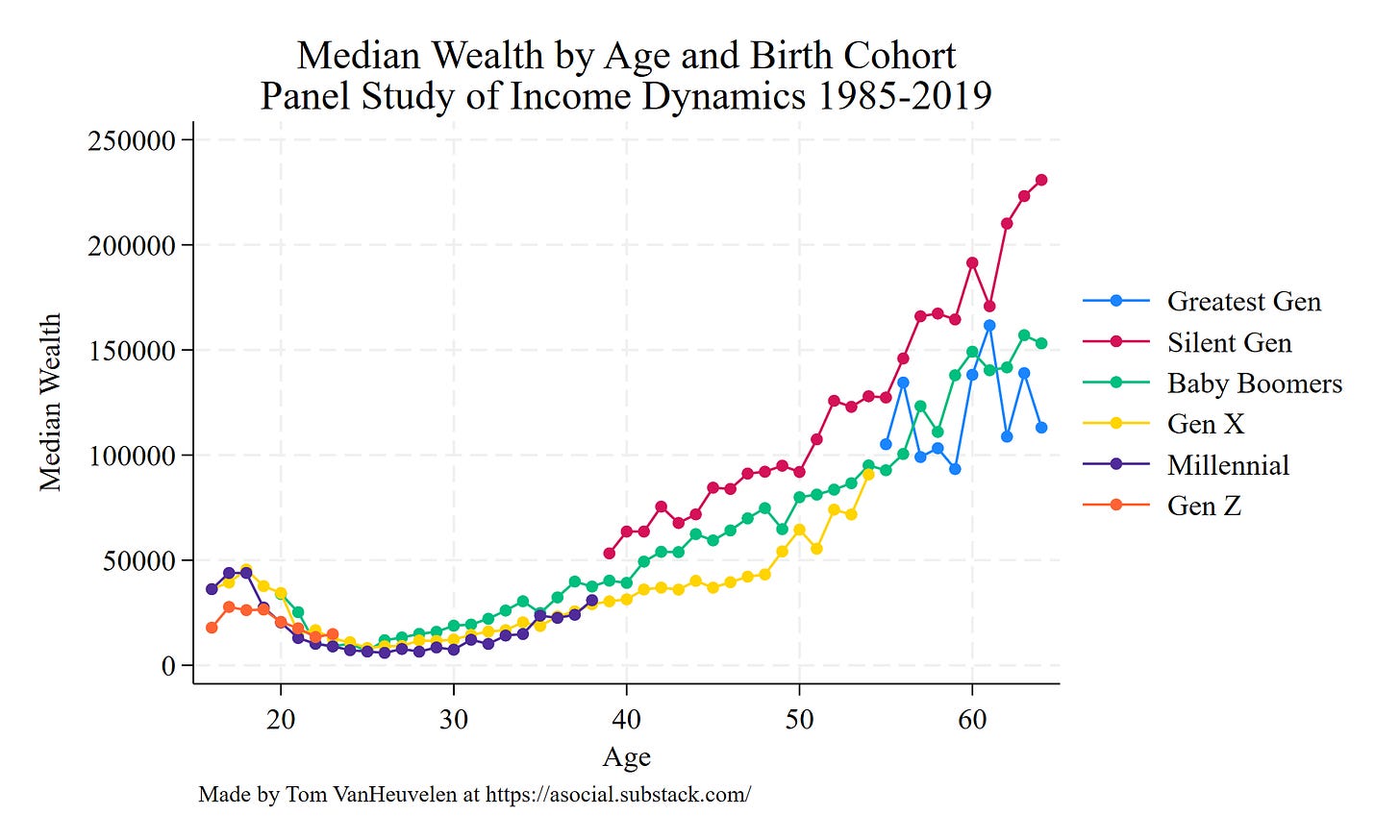

The problem that I have with both the original generation graph and Horpedahl’s reanalysis is that both clump together all of a cohort. This is obvious with the shares in the original graph, and it’s also a problem with the per capita measure as well. As a silly and simple example, if you just focus on Sam Altman and me, we are both per capita billionaires. I’m not sure how many Millennials take solace in Mark Zuckerberg’s wealth, for example. I’m familiar with the wealth measure in the Panel Study of Income Dynamics. Although it’s not perfect, it’s a high-quality dataset frequently used to study issues of wealth attainment and inequality. Let’s use it to make a rough proxy of the above graphs and focus on median wealth levels.

Well, we see median wealth rises quite a bit past the mid-40s - let’s restrict our age range to get a better comparison of the cohorts motivating the above debate.

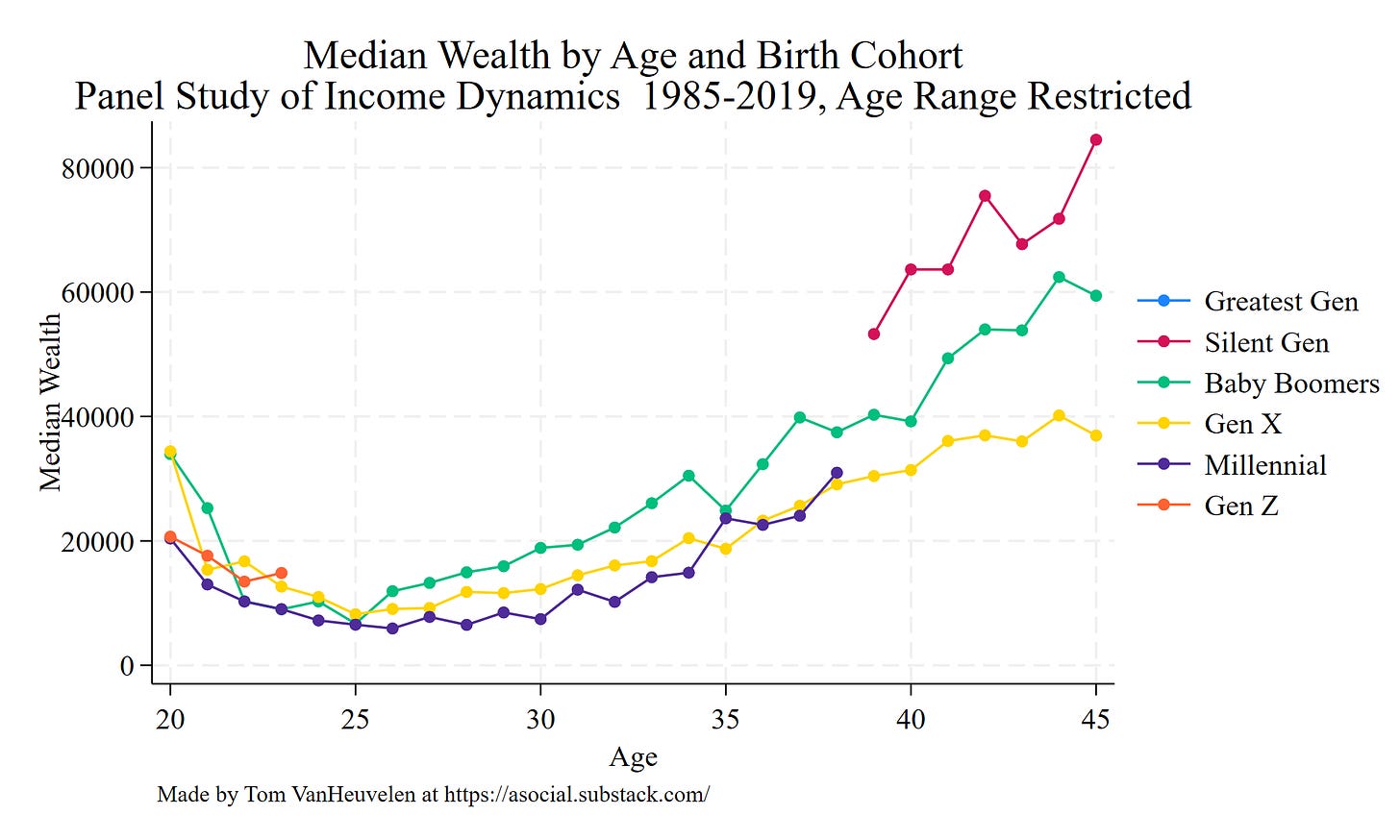

What I’m seeing is a decent decline in median wealth across cohorts, especially from ages 25 and onward (notice too that the Baby Boomers experience this too! Their 40s wealth are quite a bit lower than the wealth of the Silent Gen!). By age 30, the median wealth of the Baby Boom generation was about $20,000, and for Gen X and Millennials it’s about $10,000. I’m also seeing no evidence of catching up - the median Gen X’er has quite a bit less wealth at 45 compared to the median Baby Boomer and, especially, the median Silent Gen’er.

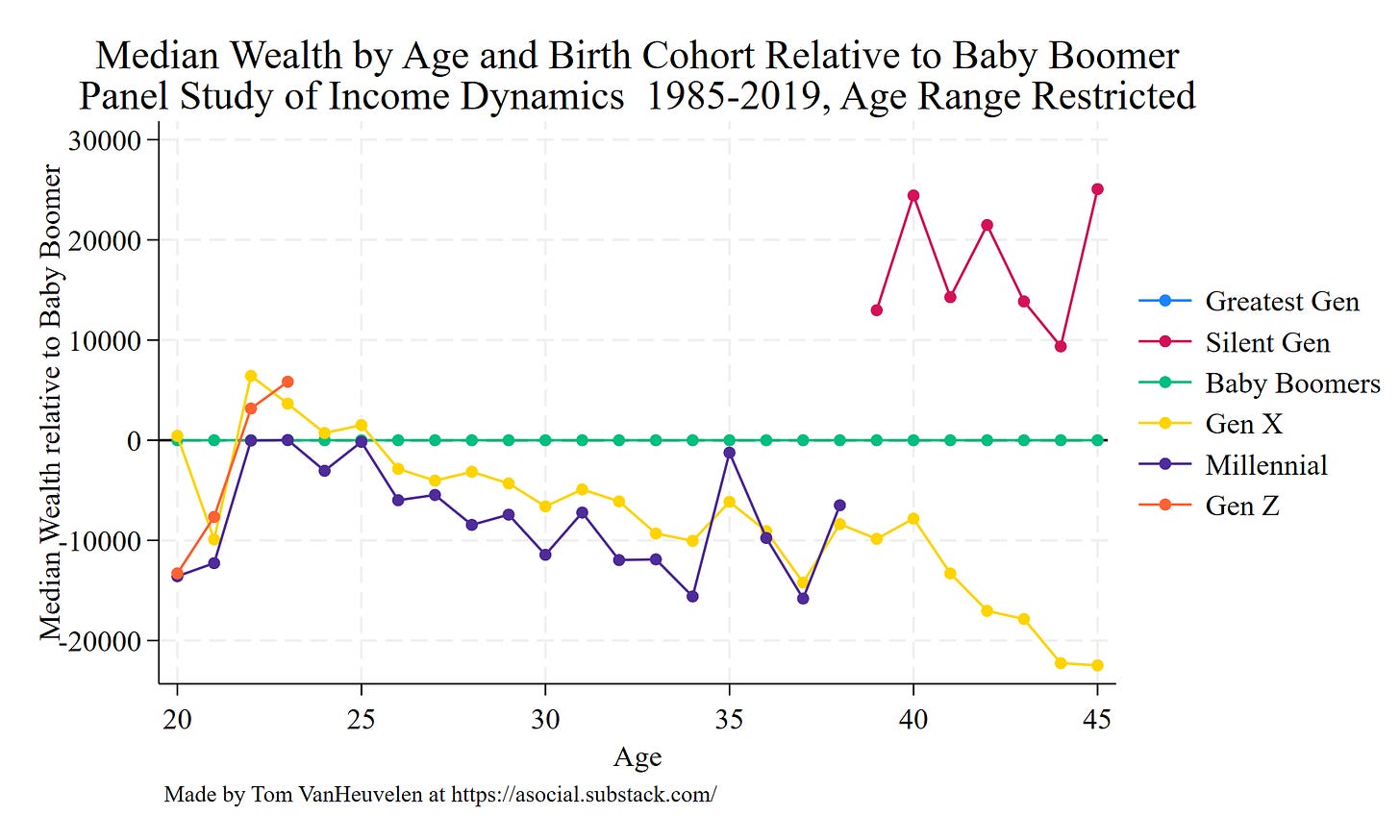

Let’s looks at these median wealth levels relative to the age-specific Baby Boomer median wealth.

For Gen X and the Millennial gen’s, we see a rough decline in median wealth levels relative to the Baby Boom cohort across age - there aren’t meaningful differences through the mid 20s and then we see a near monotonic decline through the mid 30s (Millennial) and mid 40s (Gen X) to a $10,000 and $20,000 gap, respectively.

Here are my rough conclusions:

The original wealth graph is probably a worst case scenario, and the critique that it fails to incorporate cohort sizes into its share size is reasonable.

The updated graph by Horpedahl provides a best case scenario and makes a similar error of the original critiqued graph - it asks that we blend together me, LeBron James, and Sam Altman as a big group of Millennials. Doing so risks papering over real meaningful differences that most folks feel using the extreme inequality among wealth.

If we look at median wealth gaps, we end up somewhere in the middle. We’re not in the hellscape suggested in the original graph, but we also do see real and meaningful intergenerational median wealth gaps emerging.

My median gaps aren’t the final word. Wealth is a complex distribution that refuses a snappy, single summary. It’s the antithesis of the Derek Thompsons of the world. I think that the trends listed above can all be true in different ways, for different stakeholders. It’s useful to think carefully about the multiple set of dimensions and groups of complex things like wealth distributions. They hold multitudes.