Friday fun - June 21 - Reading about the post-pandemic economy

A few high quality blog and news articles.

1. Anti-Core Inflation

John Authers at Bloomberg has an interesting set of arguments recently about why folks are still upset about the economy. He suggests we focus on “anti-core” inflation, e.g. the type of inflation that is typically bracketed out of statistics about inflation changes:

Then there’s the issue of US inflation, which we’ll learn a lot about in a few hours after you receive this with the publication of the consumer price index numbers for March. The great issue for central bankers is services inflation, particularly for shelter. Inflation is coming down; it’s not that high in historical terms any more, but it’s obvious that many people are genuinely still furious about it. Why?

Points of Return published data on food inflation yesterday that helped get at the issue, but Jean Ergas of Tigress Financial Partners suggested to me that the crux of the issue for many consumers isn’t headline or core inflation, but food and fuel. As these are exactly the categories excluded from the usual definition of the core, let’s call an index of combined food and fuel the “anti-core.” There’s a reason why central bankers find them useful to exclude, and it’s not because they don’t care; rather, food and fuel tend to be highly variable, and are in many ways beyond the reach of monetary policy. There’s also a reason why people outside central banks tend to care about them a lot. These are things that they have to buy, generally at least once a week, and any change hurts quickly. As Ergas puts it, inflation in these essentials is experienced by many as a further disenfranchisement, as adding insult to injury.

The Bureau of Labor Statistics doesn’t regularly publish a measure for just food and energy. However, they have indexes for both categories stretching back to the late 1950s. In January 1960, energy stood at 22.4 and food at 29.5. That’s fairly similar. By the end of February this year, energy (327.7) had overtaken food (276.3). Rather than attempt any subtle rebalancing, I produced an “anti-core” index of food plus energy by just adding the two indexes together. I’m sure there are better statistical ways to do this, but there are also many worse ways of gauging just how painful inflation feels to consumers.

Anti-core inflation in 2022 was about the size of the massive hit via the oil embargo in the 1970s - something we still talk about today and is a recurring player in nearly every discussion of post war economic changes I read:

We grew accustomed to low anti-core inflation post-Recession, then experiences about two decades worth of anti-core inflation in 2021 and 2022.

2. Not everyone spends on food equally

I wrote about this point previously:

Some things I've been thinking about

Very Important People from very different perspectives The sociologist Ashley Mears has a wonderful book, Very Important People: Status and Beauty in the Global Party Circuit. Mears was (is?) a fashion model and wrote this book about the strange, globalized elite world of the hyper-elite party scene, of “models and bottles,” and how models are used in th…

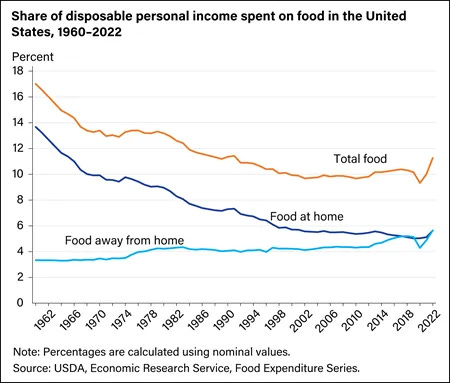

The USDA had some recent research on food spending. The big play in public-facing ideas entrepreneurs was the decline of aggregate spending on food.

I was much more interested in the income-stratified spending in recent years

Anti-core really matters for the bottom 40% of households - who spend a share on food that’s as high or higher than the aggregate stretching back to 1962.

3. Inflation hits lower income Americans harder

Authers again. He makes a forceful argument about anti-core inflation. Even if we are currently at 0 increase, inflation is cumulative and the pain of 2021 and 2022 remains:

Further, it’s been such a long time since a major shock that there’s no folk memory of what tends to happen next. Anti-core inflation briefly went negative last year and is now barely above zero, but it hasn’t gone into the kind of massive deflation that would be needed to bring food and energy prices back to where they were before the pandemic. History suggests that was never going to happen; but the pain created by a sharp upward shift in the price of essentials is real.

He then turns to chunks of inflation that will hit poorer households harder. Things that you might buy at CVS or Walgreens, or fast food:

There’s further evidence that inflation has disproportionately hurt the poorest if we look beyond the anti-core to businesses that provide goods cheaply to the less well-off. Last week, McDonald’s went to the lengths of publishing a statement asserting that the restaurant chain provided “meaningful value” to customers, following allegations that the price of a Big Mac had more than doubled since the pandemic. Meanwhile, Walgreens, a giant on US main streets operating pharmacies and selling personal goods, announced a range of price cuts, saying it understood that “our customers are under financial strain and struggle to purchase everyday essentials.” Both companies specialize in catering to the less well-off, and plainly know that their customers think prices are too high.

If we look at the level of the official CPI price indexes for products sold at Walgreens, and for fast food, we see why customers feel this way. Prices of bathroom products had stayed stable since this sub-division was added to the CPI in 1998, but suddenly took off in the last year. As for meals and snacks, they had inflated very steadily and predictably until also taking a sudden move upward. In both cases, the perception that prices are higher than they used to be, and that something unusual has happened, is fully justified by the data:

Massive and dislodging increases in recent years.

4. Presidential comparisons on economic issues

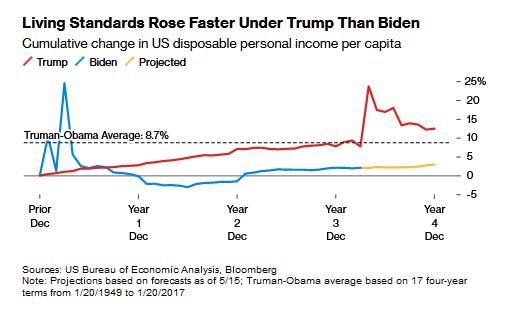

Bloomberg story that shows a bunch of economic indicators across presidential terms

Jobs are better under Biden, but I’m increasingly of the mind that unemployment isn’t as intense of a political dial mover as other more universally felt indicators

Economic growth similar - but where is the growth going if not into standards of living?

Critically, inflation’s just been really bad these last few years

Personally, I don’t love attributing economic performances directly to presidents. I feel like the hot economy during Trump’s term had a lot to do with Obama era policies, for example. But I think these help show why the population views Trump as a potential economic positive over Biden.

5. Weird Economy

The Blog A Wealth of Common Sense always has fascinating data and connections. Their recent “Animal Spirits” post had a few things that left me puzzling

The graph title asks us to look at non-managers - but my goodness, look at managers!! Multi-year decline in earnings that doesn’t seem to be rebounding. This seems like a massive story, one that I haven’t seen much written about. Is this work from home? Something else?

Is fake spending propping up economic growth?

These figures come from the Overshoot substack - here’s the author Matthew Klein

Intriguingly, more than 40% of the growth in real PCE in 2024Q1 is currently attributed to finance and insurance plus net nonprofit spending. That is the highest share coming from this subset of (mostly) imputed categories since 2011.

In nominal terms, rapid growth in non-market-based PCE (16% annualized) has offset slowing growth in market-based PCE, such that the headline growth rate has remained stable around 6%. The current pace of growth in non-market-based PCE is much faster than what would be required to “catch up” from the slowdown in 2023.

This is a bit outside my comfort zone, but I feel comfortable claiming that this is not a robust person-centered source of economic growth. Smells a lot more like the financial mischief of the early 2000s.