Some things I've been thinking about

Very Important People and Very Different Readings, The 2014-2020 Vibecession, Food Costs, Kids Movies

Very Important People from very different perspectives

The sociologist Ashley Mears has a wonderful book, Very Important People: Status and Beauty in the Global Party Circuit. Mears was (is?) a fashion model and wrote this book about the strange, globalized elite world of the hyper-elite party scene, of “models and bottles,” and how models are used in this party scene to boost the status of men.

It’s a great book that touches many different areas of sociology - inequality (obviously, it’s about the hard to observe hyper-elite in society), culture (it’s a very nice update on Veblen’s conspicuous consumption), gender (obvious issues of gender relations, beauty, sexuality in hyper elite spaces), and globalization.

There were two recent discussions of the book that are fun to observe next to one another.

The Socialist magazine The Jacobin has a podcast, The Dig, and they recently interviewed Mears.

On the other side, the wild book review Substack, Mr. and Mrs. Psmith, interviewed the sociology professor Gabriel Rossman about Mears’ book.

Mears’ book, but also these dueling reviews, are really worth checking out. I just loved listening / reading these back to back to see their different emphases. The Dig focuses on the very real problems of gender dynamics, the racial stratification of who gets to be a model and the barriers faced by club runners / model recruiters, the weird excesses of wealth demonstration, and the policy failures that have allowed for the production of such excessive wealth. The Psmith review somehow gets to this zany place:

In so many areas of life, we are obsessed with collapsing intrinsically high-dimensional phenomena onto a single uni-dimensional axis. You see this a lot with the status games that leftists play around privilege and oppression — I feel like a rational leftist would say that a disabled white lesbian and a wealthy scion of Haitian oligarchs are just incomparable, each more privileged than the other in some senses and less in other senses. But no, instead there’s an insistence that we find an absolute total ordering of oppression across all identity categories, a single hierarchy that allows us to compare any two individuals and produce a mathematical answer as to which one is more deserving of DEI grants. My hunch is a lot of the internal tensions and bickering within American leftism are actually produced by this insistence, which makes sense because it’s totally zero sum.

Just so interesting to see how a common academic study was processed so differently from these two sources

Consumer Sentiment, now and then

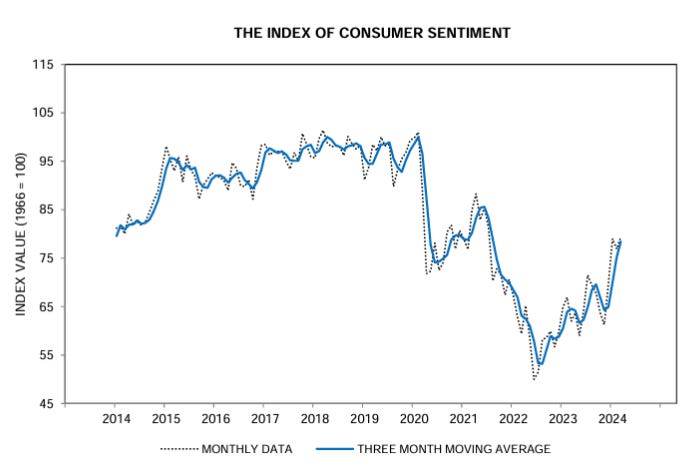

Consumer sentiment is rebounding - it’s now at about 80% the pre-pandemic level.

Two things are interesting to me. First, major purchases seem to be some of the big drags on rebounding consumer sentiment. Below is the trend in perceived buying conditions for a house:

Never been worse - rival time was the early 1980s.

Part of this pessimism is due to high housing prices

Another part is high interest rates

Folks were pretty pessimistic about interest rates in the 1980s - more so than today. But folks today are pessimistic about both interest rates and prices today, something that wasn’t the case in the 1980s.

Interest rates are also driving pessimism among car purchases:

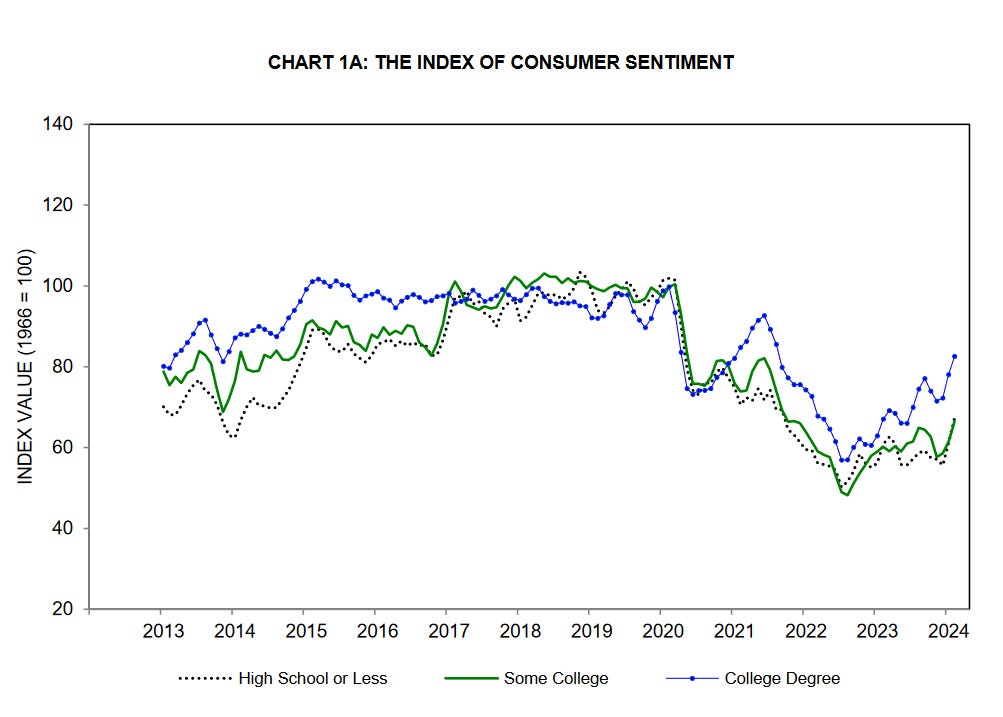

The second thing I’ve been thinking about regarding consumer sentiment: the totally wild historical anomaly of 2015-2019 economic conditions. Take a look at the consumer sentiment trends from the last ten years, stratified by educational attainment.

The rebound of consumer sentiment has been mostly concentrated among folks with a college degree or more. Their consumer sentiment has bumped back up to ~ 2014 or 2015 levels. Folks with some college and a high school degree or less have had consumer sentiment bump back less. Two things: 1. Look at the period of 2017 to 2022. It was a period where folks with different education levels had roughly similar consumer sentiments. 2. The earlier bounceback of consumer sentiment among folks with a college degree is pretty common after an economic downswing. Take a look at the 50 year trend:

College folks bounced back more quickly after the early 1980s recession, after the dot com recession, and after the great recession.

The thing about the first point - if we look at the entire period where consumer sentiment was measured, 2017-2022 was one of the weirdest periods of sentiment in modern history. Less educated folks had higher sentiment than more educated folks! It’s easier to plot the difference across education groups to see this point:

2017 to 2021 was really the only period where folks with a high school degree or less were more positive about the economy than folks with a college degree or more.

College and some college are more similar, and we’ll occasionally see the “some college” group have higher sentiment. However, 2017 to 2021 was a weird period of a longer stretch of time where less educated folks felt better about the economy than more educated folks.

If we look at the levels of consumer sentiment, it appears that folks with a college degree or more may have become historically pessimistic from about late 2015 onward. Consumer sentiment has been used to argue about a potential “vibecession” between 2022 and 2024. However, this is a period where things start to look a lot more normal, with higher educated folks becoming much more positive than less educated folks. It seems that the real vibecession to understand is the one among higher educated folks between 2014 and 2021.

Food spending

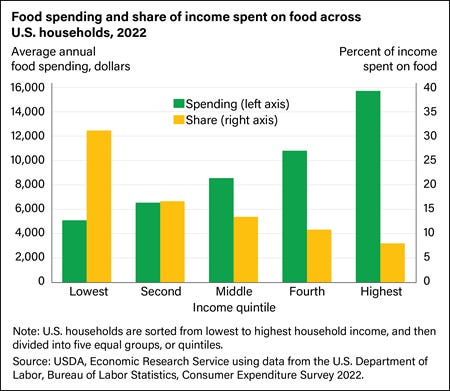

A few weeks ago the USDA released an interesting finding - a time series of the percentage of income spent on food.

This led to a few interesting discussions, particularly by folks like Noah Smith and the blog Wealth of Common Sense.

Some of the interesting points: (1) the rise of spending seems to come from “food away from home,” not “food at home.” Eating out is more expensive - as everyone can attest! (2) the share of income going to food has declined substantially over the past several decades - from 17% to 10ish% overall, and from 14% to 6% for food at home. A Wealth of Common Sense extends this out even further, showing that food expenditures were upwards of 50% of income in the early 1900s.

I think it’s worth noting another piece of the food spending puzzle - food expenditures vary massively by income level:

We’re looking at the share of income spent on food among folks sorted into five groups - the poorest 20% of Americans through the richest 20% of Americans. The richest Americans spend a lot more money in absolute terms on food - $16,000 annually versus $5,000 annually among the poorest group, but as a share of total income, the richest spend only around 7% of their income on food. This contrasts with about 30% for the poorest group. Even for the second poorest group, we see that food expenditures are around 15% of total income, which is near the level of overall food expenditures of the US in the early 1960s.

Lower income folks also eat out less frequently, according to Gallup data

And according to data from Statista, the relationship between total money spent and share of overall income for eating out costs are similar as those on overall food expenditures:

I believe these data come from the same source as the USDA - if I just eyeball the two - it looks like a larger share of total food expenditures among high income households go to eating out, while a larger share of total food expenditures among poorer households go to food at home. I think that means there’s more slack in higher income households to pull back, scale down, etc.

Thus, when we see a debate about the importance of food prices, it’s useful to remember that there is not a simple answer - increase in food costs are both largely not terribly consequential and quite consequential at the same time, depending on who you are talking about.

The Cultural Knowledge Gleanable in Kids Movies

This is funky, but I’ve enjoyed watching many, many kids movies that have been produced over the past six decades with my kids. It’s wild to see the assumptions that are used to establish plots, or justify action, or establish a setting that reveals the latent assumptions of how the world operates in a particular era, or what the culture privileged at a certain time, or the types of social problems that are worth grappling with and incorporating into a fictional world aimed at a child. A few silly examples:

The Little Giants (1994)

What a classic. A small-town football team of rag-tag children comes together and defeats the fancy and more athletic bully football team. The thing that I noticed when watching it: the movie is set in a fictional small town, Urbania, Ohio. This small town is unproblematically depicted as having a robust, diversified local economy, with local businesses, a vibrant middle class, a local economic elite, even business dads who go on long work trips.

This is such a different depiction of small-town America than I’m used to seeing these days - if small-town America is shown in popular media, the portrayal is usually about its demise: people dying of heroin overdoses, small-town poverty, or, less frequently, the tiny magisterial places that have been overrun by billionaires and the constellation of low paid migrants tasked with catering to their needs and whims. Vibrancy is for the affluent metro areas these days, I’d argue.

I thought I’d take a quick peak at some county-level data from the US Census and American Community Survey between 1980 and 2020. I grabbed per capita household income (inflation adjusted) and county population. I sorted counties into 10 bins based on their year-specific populations. I also sorted per capita earnings into low, medium, and high (low would be the 40% of counties with the lowest per capita incomes, medium is the middle 40-70%, and high is 70% and more). I then looked to see what percent of each county population-bin fell had each of these earnings levels:

I highlighted the second-lowest population bin - I figured this would be the place where small-town Americana would sit. We see in the middle graph that the 1990s were a bit of an odd time, where these smallish places held the most “middle income” earnings levels. So in 1994, it’d be totally reasonable to set a movie about a socioeconomically vibrant and diverse local economy in a small town! You see that becomes less and less the case in future years.

The Croods (2013)

Caveman family is traditionalist and extremely rooted to routines. They are hostile towards change, disruption, and innovation. Their caveman environment changes, forcing them to go to new places and develop new skills, and they encounter Guy, a young and thin caveman who is basically master of the universe and creator of material abundance by using his brains, ideas, and inventions. Guy is the ultra-disruptor: looked down upon for lack of brawn, yet his positive attitude, emotional intelligence, conceptual thinking, and ability to translate abstract concepts to small practical gadgets saves the day.

It’s shocking that this era feels like it is behind us, but this is such an Obama-era techno-optimism story: tech innovators with their inventions are the heroes. The good guys are the ones who pursue knowledge and ideas: those brave disrupters are leading us to a future of equitably shared enlightenment and prosperity. Meatheads and traditionalists are unfortunate souls ignorantly tethered to the way things were and need to get with the program. To the highly educated go the spoils. And - according to the 2010s cultural assumptions - that’s a good thing. A logic that makes sense in a time where aggressive college expansion is moving along, where tech had yet to take its reputational hit, and when the college earnings premium had yet to stall out for many.

Migration (2023)

I legitimately love this movie. It’s about a duck family that migrates - meeting new friends, finding adventure, overcoming adversity, and coming together as a family. They travel to a big city and meet pigeons. And they ultimately end up in the Caribbean, where they have so much fun that they decide to go on another spontaneous vacation.

The generative drama is that the duck father is unwilling to leave his home because he is afraid of things that are outside his home. He has to learn that this fear of leaving home is unfounded and that it’s ok to leave home to unfamiliar places.

I am going to go out on a limb and guess that, “An adult is afraid to leave their house, and the big drama is generated by them overcoming their fears and bravely leaving their house,” is very specific to a culture just leaving the pandemic with a core message of “stay home, stay safe.” I’m guessing a similar pitch would be seen as uninteresting or not sufficiently dramatic in 2006.

A good explanation for the late 2010s college/high-school flip in consumer sentiment is Trump, right? Partisanship came to dominate perceptions of the economy. I can't think of anything else so period-specific.