Inequality Readers. Piketty Strikes Back

Has inequality grown over the last half century? The great debate continues!

One of the great debates in inequality research gets at a fundamental question: has inequality increased since the 1960s?

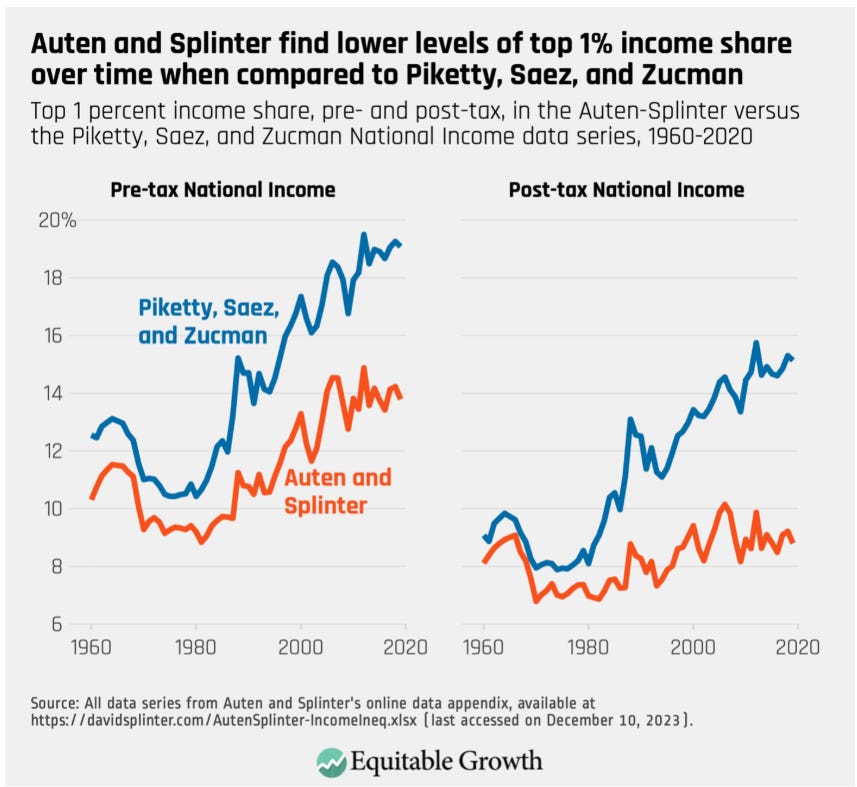

Auten and Splinter have made a bold claim and an incredibly important contribution to the inequality literature; when you take into account the full picture of income, as well as government taxes and transfers, inequality today is barely any different than it was in its early 1960s levels. They claim that Piketty, Saez, and Zucman (PSZ)’s famous work dramatically overestimates the rate of inequality growth. Below is the culmination of their empirical reexamination of PSZ.

Their argument claims that the work of Piketty, Saez, and Zucman has overinflated the share of pre-tax income going to the top 1%, and underinflated the degree to which taxes and transfers reallocate income away from the top 1%.

I have written about this debate a fair bit. Here’s one

What the heck is happening to inequality VI. Inequality _never_ increased?

Some of you might remember the brief controversy in the 2010s caused by Wisconsin Congressman Paul Ryan’s proposal to radically simplify the tax code - making it simple enough to fit on a postcard.

And another (5th article discussed):

And another:

Monday - July 22 - One Good Read

A critically important debate has been going on between two groups of economists. Piketty, Saez, and Zucman (PSZ) are very well known scholars of inequality. They popularized the stylized fact of the dramatic rise of inequality among the top 1% of income earners over the past half century.

And another:

Does health insurance reduce economic inequality?

Does the American healthcare and health insurance system redistribute resources in a way that reduces economic inequality? I’ve been stewing on this a bit since reading a very important article on inequality change by Auten and Splinter. The main thrust of their argument is agains…

PSZ response

Well, PSZ have read the Auten and Splinter (AS) work carefully and written a response.

The key issues relate to the handling of untaxed, sometimes unobserved, income. We’re in a world where researchers need to make distributional decisions - does this chunk of unobserved money go mostly to high income earners, evenly across the income distribution? Let’s go through PSZ’s response, which I found rather convincing. PSZ attributes most of the differences between their and AS’ conclusions to three major issues:

The treatment of untaxed private business income. We’re in the depths of assumptions and business income reporting minutia here. But decisions here account for 40% of the difference.

Untaxed capital income. PSZ say that decisions for distributing this type of money across households account for about 20% of the discrepancy.

The catch-all “non-cash, notional income” allocation of national income (think of how to handle discrepancies between micro- and macro-reports of income, how to handle the national debt, how to handle public spending on parks and the military). PSZ say that AS’ blanket allocation is functionally a universal basic income that necessarily produces a 0% poverty rate, which is incorrect. This decision accounts for most of the remaining 40% gap.

Business Income

Oh yeah, who’s ready to talk about fiscal depreciation!

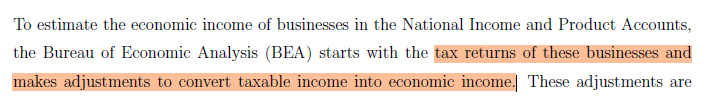

Much of the debate between PSZ and AS occurs around decisions to make income measures across various data sources comparable in order to get a holistic picture of the total distribution of American income.

One of the key adjustments made by the BEA is depreciation:

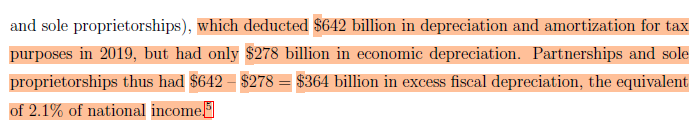

PSZ argue that we need to separate two kinds of businesses - partnerships and sole proprietorships, to get a true understanding of inequality trends as a function of business depreciation. That’s because these are two kinds of businesses that tend to exist at two places in the earnings distribution (partnerships are typically the domain of higher income earners - think of a large real estate holding, and sole proprietors tend to be lower income, think of a freelancer), and the two types of businesses have different contributions to excess depreciation:

Depreciation is a partnership thing, not a sole proprietor thing.

This partnership-depreciation connection is a policy outcome:

The contribution of partnership excess depreciation to total national income has grown over time. The contribution of sole proprietorships has stayed the same, near and slightly below, zero:

The 1986 Tax Reform Act changed business incentives, and also resulted in the forms of business to change:

This results in growth of S-corporations and partnerships, which grows the importance of this excess depreciation.

PSZ notice that AS allocate excess depreciation to owners of sole proprietors, not to partnership owners.

That is, you might allocate the income of a massive real estate holding company to a freelance wedding photographer. Probably a suboptimal decision.

In their appendix, some case studies of high-earning depreciation

This matters, since partnership owners and sole proprietors are in different locations of the earnings distribution:

There are various additional decisions to make about the uncertainty of partnership owners (these business relationships tend to be intentionally highly complicated, sometimes involve offshore tax havens, sometimes involve hedge funds, sometimes involve, complex holding chains), and PSZ go through various decisions one could make allocating the uncertain income components. They come down on a range based on reasonable decisions, and notice that AS’ allocation of this income to top income earners is very low.

Untaxed Income

Next up, how to handle underreported income? Untaxed business income is nearly 7% of total income in national accounts. PSZ note that business income is highly concentrated (held by very rich individuals). Why would taxed business income be highly concentrated but untaxed business income be very not concentrated?

Do we really think that lower income Americans have a high holding of untaxed business incomes but a low holding of taxed business incomes? It seems unlikely.

A good deal of this issue again relates to the growth of S-corporations as a major source of high income earners’ incomes:

PSZ argue that AS understate the amount of tax-evasion income held by the top 1%:

Then there is capital income - income from asset ownership. We should expect this type of income to be highly concentrated among richer households. PSZ notice that AS allocate untaxed capital income in a highly egalitarian way - something PSZ argue is probably extremely unrealistic. Again - why would taxed capital income be highly unequal and untaxed capital income be highly equal?

It seems that AS allocate a good chunk of this type of income to both funded and unfunded pensions. But technically, unfunded pensions don’t have assets. So it’s not clear whether they’re really income that people have.

This is a really tricky question, in my opinion. And one where I’m a little more sympathetic towards AS. These plans will eventually be paid out, at least in some states, I would suspect. How do we treat an individual with $1,000 saved for retirement versus another with $0 saved but a public employment pension plan promising $1,000 in retirement? I guess the latter could eventually go belly-up. But this is one point I don’t really feel comfortable simply granting to PSZ.

Non-Cash Notional Income - a National UBI?

There are some accounting differences between PSZ and AS:

The government deficit is distributed by AS to equalize income, which PSZ argue is unreasonable.

Finally, does the US spending on the military, prisons, parks, and education represent a UBI? If so, the allocation by AS functionally ends poverty in America. Don’t tell Matthew Desmond.

An unreasonable decision, in all likelihood. PSZ says - really only education might be reasonably considered such a UBI, and it’s only 30% of the total.

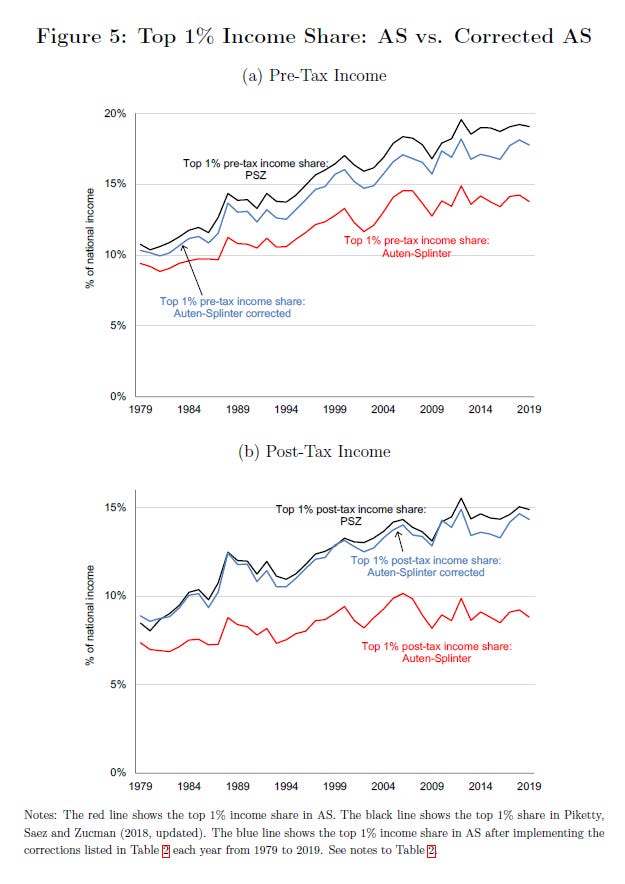

Where we stand

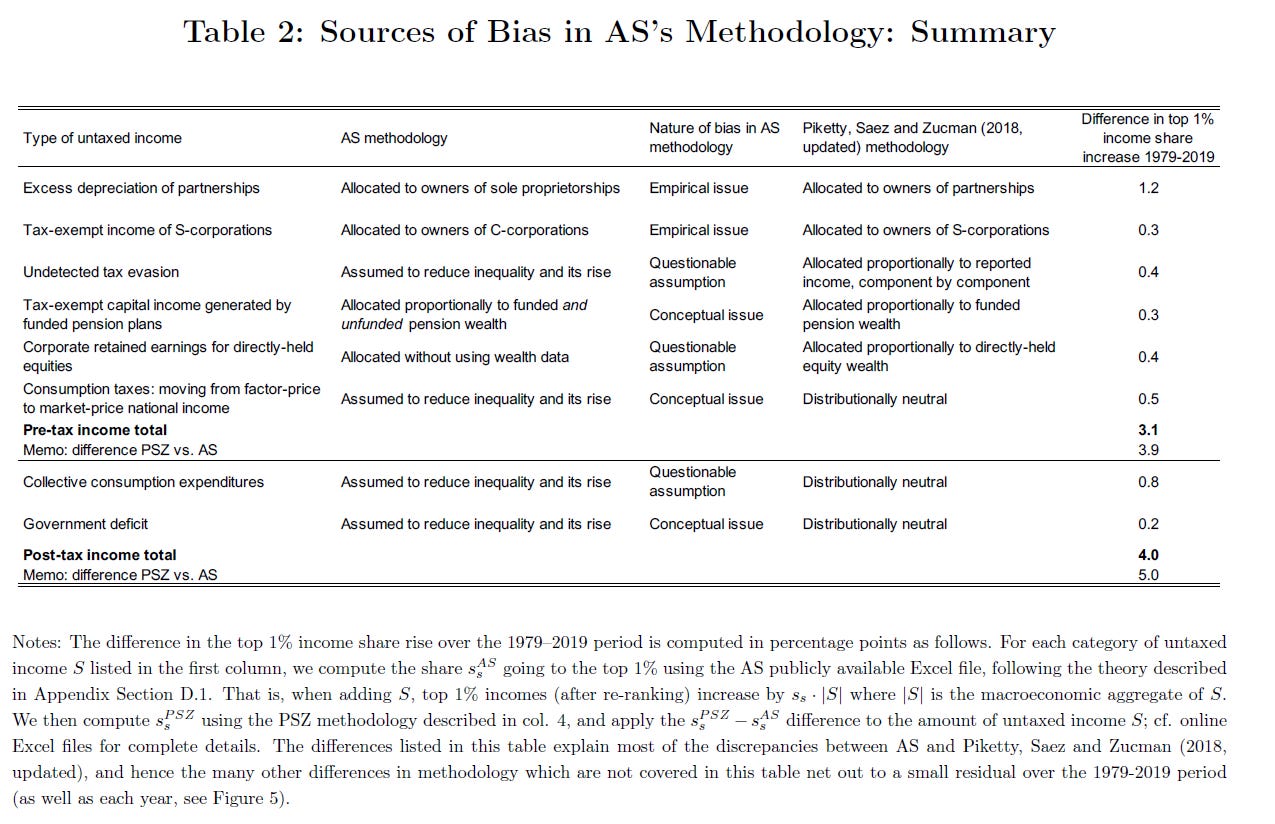

Let’s take a look at this summary table of the difference between AS and PSZ

We’re looking in the far right column at the change in top 1% income share over time (e.g. how much inequality has grown).

The issues raised in this article accounts for 3.1 of the 3.9 gap in pre-tax top 1% income between AS and PSZ, and 4 of the post-tax top 1% income. I’d take away the 0.3 of the unfunded pensions, but that still results in (3.1 + 4 - .3) = 6.8% higher top 1% change over time. The total discrepancy between AS and PSZ is 3.9 + 5 = 8.9% , so PSZ have directly addressed about 80% of the difference.

Aside from pensions, I find PSZ’s corrections to be reasonable. It is thus really difficult to claim that post-tax income has remained basically unchanged.

A nice conclusion: all observable forms of income have become more unequal over time. The only way to claim income has not become more unequal is to claim that unobserved income has had a strong equalizing effect. Which is pretty unlikely.

Even if PSZ levels of growth are overstated, it’s really hard to believe that the general thrust of the conclusion - rising inequality since the 1960s, is incorrect. AS have made a valuable contribution to the inequality literature, but I just don’t think that their claim of non-growth holds up. Inequality, both before and after taxes, has increased. Has it increased as much as the original PSZ statement? Probably not. Can we take some of AS’ critiques to discount the magnitude of the overall growth? Probably. But the most reasonable conclusion is that we live in a highly unequal world, one with more inequality than in the recent past.

PS

If you made it this far, you might be the kind of person who’d enjoy this post by Austin Clemens at the Washington Center for Equitable Growth, which does a great job going into the weeds of the contrasting assumptions of unreported income between AS and PSZ.