Monday's Good Reads - That Giant Sucking Sound

NAFTA did nothing. NAFTA did bad. NAFTA did good.

These days, when you hear someone say, “That giant sucking sound,” I’d say that refers to the United States. We kind of suck at the moment. Some of this has to do with the current trade war, but it also has to do with our high inequality, declining education standards, low trust, and high isolation.

Back in the 1990s, the Giant Sucking Sounds had to do with debates over trade, specifically NAFTA:

American politics is wacky! Can you believe there was a Clinton-Bush-Perot election?!

What is NAFTA? Here’s a little video explainer:

Did NAFTA do anything, especially in terms of wrecking American manufacturing and setting the table for the rise of the anti-trade Trump Republican party? People certainly thought so! But opinions ranged from - it was a disaster to it was an economic miracle to it was a nothingburger.

Perhaps you’ve heard, but free trade and tariffs are in the news. So I thought I’d cover a few interesting writings about NAFTA, building up to a very interesting new article about the employment and partisanship effects of NAFTA exposure.

Yglesias is skeptical of big NAFTA effects

Matthew Yglesias is a political commentator and maintains an interesting blog, SlowBoring. He is skeptical of a large NAFTA political effect, driving blue collar workers to Trump.

He argues that NAFTA just didn’t do much to make Democratic politicians unpopular in the Midwest

He says that the timing between NAFTA and Trump’s anti trade rise doesn’t add up. He also says that narrow NAFTA effects can’t really explain broad political shifts in sentiment.

Politically, the more plausible argument is that working class Democrats swung against cultural liberalism (e.g. gender, race, and sexuality things).

He goes on to argue that NAFTA may have had negative effects in industrialized small towns. But there would have been structural problems anyways. And now that the toothpaste is out of the tube, it looks ridiculous to ask to do the opposite of passing NAFTA - e.g. making a small town a bit richer at the expense of more expensive cars and less wealth in wealthier places.

Making the NAFTA affected places better off will make everyone worse off, which is a massive trade off that is not worth it.

Bruenig, Contra Yglesias

Matthew Bruenig is a thoughtful and intelligent writer who cares a lot about egalitarianism and robust welfare states. I like just about everything that he writes. He wrote a blog post on NAFTA responding to Matthew Yglesias’ blog post about NAFTA.

Bruenig says that the late emergence of anti-trade Republicanism is reasonable:

Bruenig also casts doubt on the argument that NAFTA is a targeted effect, whereas other cultural issues are broad effects.

I’ll quote him a bit more - trade can absolutely get bundled into cultural liberalism isuses:

Nafta Wrecked Things, Say Some Economists

Next we have an article by Choi et al. arguing that, actually, NAFTA may have had a negative impact on local employment.

I’m a fan of Gavin Wright - he wrote a very interesting economic history book about the impact of Civil Rights legislation in Southern labor markets.

In this article, Choi et al. argue the following: (1) NAFTA reduced employment in counties that were vulnerable to NAFTA-based disruption (2) people didn’t relocate out of disrupted counties (3) we see a shift onto things like disability in counties disrupted (4) we see a rightward turn among folks in counties disrupted by NAFTA.

They construct a vulnerability index to measure a county’s potential exposure to NAFTA policy change. It starts with this:

Revealed comparative advantage for a particular industry. Basically: the numerator is a ratio of: exports from Mexico to all non-US countries for a particular industry divided by exports of all non-Mexico countries to all countries except Mexico and the US.

The denominator adjusts for the ratio of all of Mexico’s share of exports not limited to a specific industry.

This is then spun into a measure of vulnerability

Vulnerability combines the relative advantage measure with information on county-level employment in a particular industry (e.g. are lots of folks in Cook County employed in an industry where Mexico has a large comparative advantage), and the 1990 tarrif rate for that industry in 1990. So this measure looks at (1) the Mexican comparative advantage relative to (2) the potential for NAFTA employment disruption and (3) the amount of protection against such disruption prior to NAFTA.

We then look at this vulnerability measure in country groups over time. First, we can see the extent of tariff protection across the vulnerability distribution before and after NAFTA passes.

Unsurprisingly, NAFTA had a big impact on the counties with the highest protective tariffs. Removed these protections, ramped up free trade.

Here’s the vulnerability measure distribution

To me, it looks like NAFTA took a massive swing at manufacturing and agricultural places. Look at the Southern exposure.

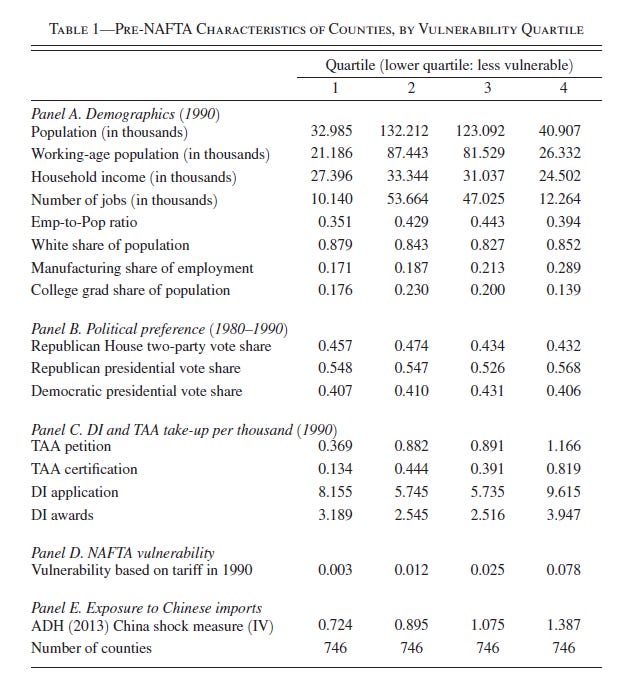

We can look at the characteristics of these places prior to NAFTA.

1= least exposed to NAFTA, 4 = most exposed. We see that the most exposed had the lowest income, and the lowest education level. It didn’t look different politically from other places (panel B).

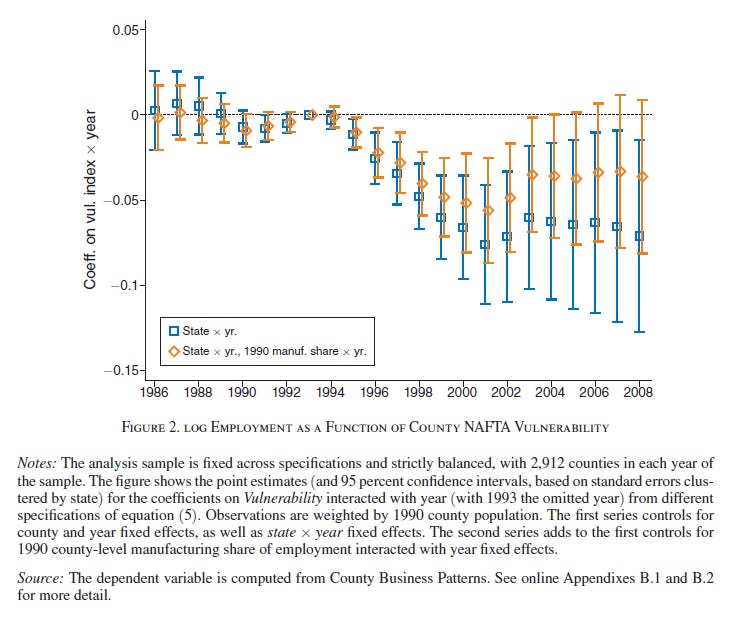

Then, we get to the first big finding: their vulnerability index predicts decline in employment following NAFTA.

depending on the controls (yellow figures), the effect disappears a decade later, but generally we see at minimum a decade long decline in employment among places vulnerable to NAFTA trade.

The below is an appendix figure, but they replicate their data using high quality individual-level panel data, the Panel Study of Income Dynamics:

I find this replication very persuasive and am not sure why it wasn’t in the main paper, nor what it isn’t the centerpiece of a second paper!

Surprisingly, people did not leave these places with declining economic conditions. There is no variation of migration across vulnerability after NAFTA.

We do, rather, see a rise of disability insurance applications:

Then, the authors get a little funky. They turn to political data. And they find a rightward turn among counties with greater vulnerability post-NAFTA.

They dig deeper into attitudes, which, in my opinion, gets a little off the rails and has a lot of uncertainty. But in general, we see that NAFTA potentially contributed to the reshaping of political coalitions in exposed places, shifting folks towards the Right.

The authors’ conclusion:

Perhaps NAFTA did do something.

Twitter Economists Fight Back

Economists love a fight. And thus, economists fought on twitter using long posts about methodological minutia.

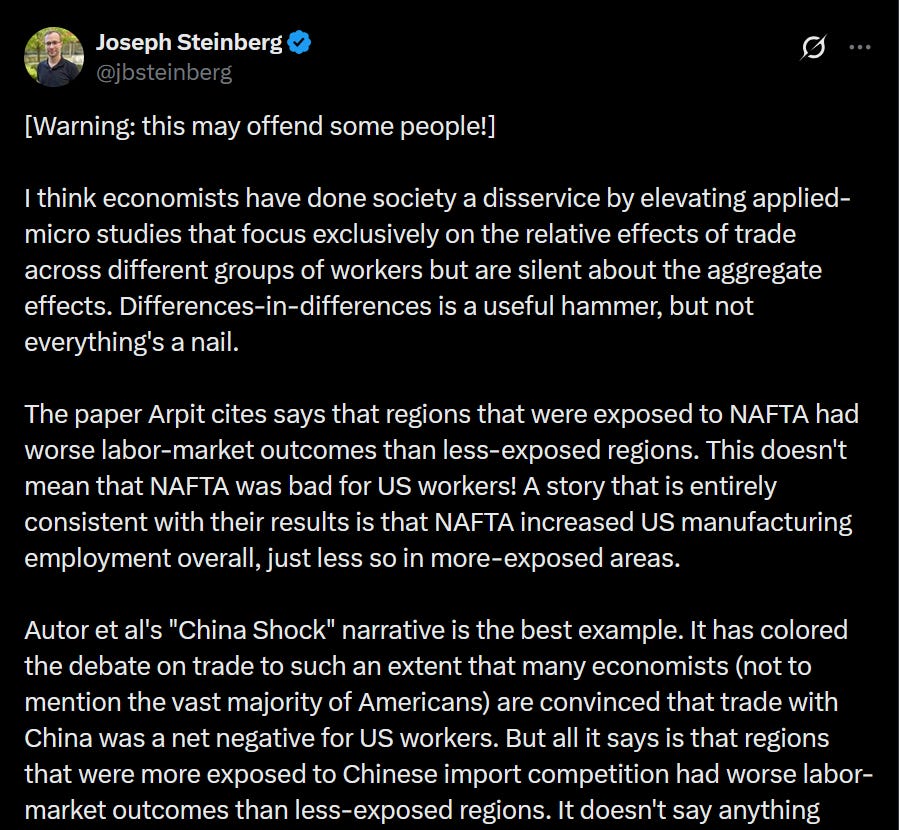

Although I’m not sure how much I fully agree with this response, I like this response a lot. It is thoughtful, generous, and pushes my thinking in directions I would not have otherwise gone. Also, it is perhaps a bit radical, at least from my perspective in sociology!

Here is Steinberg’s general argument, as I understand it: regression techniques compare counties more and less exposed to NAFTA and found that more exposed counties did worse. But part of the statistical technique “netted out” time and average county effects. Thus, all counties could be improving at different rates.

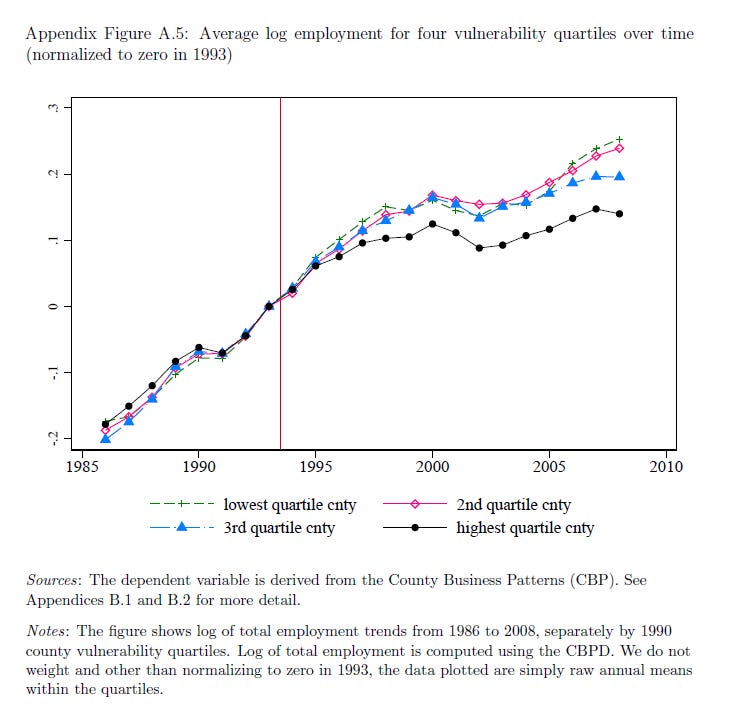

Is this point valid? I’m not so sure. I looked at the Choi appendix and found this figure:

Even if we just look at the descriptive trends of employment across counties, doesn’t that “most exposed” black line kind of smack you in the face? My metaphorical description - these four lines were walking lock step together until 1994. At that point the black line got punched in the mouth, stumbled around until 1998, then fell down. I mean, maybe something else is going on, but it sure looks like we can see an absolute smack in the face, not a difference in relative rates of improvement, right?

Also - this graph counters Yglesias a bit. It looks like NAFTA pretty much just knocked exposed counties from the rest. At least in terms of employment, we don’t seem to see a compensating boost among the less exposed counties.

Steinberg also makes an interesting argument - perhaps trade improved things overall by lowering prices.

Is that a reasonable counterhypothesis? In some ways, absolutely yes. I mean, personally, I love low prices. I tend to choose them over premium prices, if I’m given the equivalent choice. So it matters! It is a real counterargument that needs to be taken seriously. Lower costs can absolutely improve welfare.

With that said, a few responses come to my mind:

“Yes, you are on SSI instead of working, but look at all the cheap shit at WalMart” sounds like how I would satirize an economist. It is a response with a little bit of cruelty in it.

I would think that these claims require empirical backing. Steinberg provides two links - one showing that Chinese import competition reduced prices through competition and reduction of markups, with price reductions pronounced among products catering to lower income consumers. The other broadens out focus on Chinese import competition to supply chains and non-manufacturing employment, arguing that overall wages and employment in the US improved because of Chinese import competition. I am not an expert on this topic, but my gut says that the truth is probably in the middle between extreme claims of Chinese trade devastation and these more positive arguments. And of course, these studies don’t directly contradict findings on NAFTA. I would want to see more direct empirical evidence that the findings by Choi et al are more directly refuted at the aggregate. I think it would be tough to get a valid aggregate welfare argument empirically tested, but it should be done!

Even if prices overall declined, the figure of employment and the transition to disability suggests an inequality-producing effect of NAFTA, right? And even if one gets a bit better off, or only some industries in one’s town were devastated, the imbalance between places more or less exposed probably made folks feel relatively worse off, which is a real outcome. Think about what I’ve written in the past about poverty measures. Relative deprivation is an absolutely real thing with real consequences.

Monday - One Great Read - Poverty Measurement

Back in 2020, Shawn Fremstad wrote a fantastic report about poverty measurement. Thought I’d go through it here.

I kind of love seeing debates in economics where folks respond to microeconometric methods by saying, “You’re not looking at the big picture!” Do they know that many a critical sociologist was saying the same thing in response to the demands made by the credibility revolutionists in micro-econ? Perhaps I could argue that Steinberg is similarly not looking at the big picture, as he doesn’t aggregate up to broad issues of neoliberalism and the barreling freight train of modernity.

Although I’m pushing back a bit here, I do think that Steinberg raises a valuable critique to be taken seriously.

Where does this leave us

What did NAFTA do? I keep thinking about the Yglesias and Steinberg arguments that ask us to zoom out and think about the aggregate effect of the policy change. Let’s take such a macro perspective, and let’s use a metaphor.

Here is US life expectancy over time.

You can see that ... well ... COVID had a big effect. But on the aggregate, was COVID so bad? I mean, life expectancy is still, what, at mid 2000s levels? And why was everyone freaking out about an American health crisis prior to COVID? Overall, I just see a gradual increase over time!

(obviously, obviously I think COVID was bad. And I was very worried about the changes to American mortality in the 2012 - 2019 era. This is a pedagogical point!).

I mean, if you zoom way far out into the aggregate, you can smooth over a lot of meaningful local details and argue, “everything’s basically normal.” And such zooming out often has great value! It’s important to remember, for example, that poverty has dramatically declined. And that we live with an extraordinary food and nutrition production system.

But massive social problems can happen within zoomed out trends. Social problems that are deeply consequential. My hunch is that NAFTA probably did have a real, targeted negative impact on places exposed. That had immediate consequences for folks in those counties, increased inequality - which is bad for everyone - and reduced trust - which is bad for everyone. Was it carnage and the hellscape some describe it as? Probably not. Were there benefits? Undoubtedly so. But in this mix of uncertainty, some very real negative consequences need to be included in the ledger.

We tend to conflate NAFTA with China MFN, which happened at the same time, so it makes sense. And maybe the distinction is not very important because what we're really discussing is why there is a turn against trade and globalization. But, I do think NAFTA and China have had different effects and, I suspect, the latter has been bigger and more disruptive. [I'm not positive about this, and trade flows are bigger with NAFTA v. China. But they look different, with US running bigger deficits with China.] So looking at exposure to NAFTA narrowly, probably isn't that useful. Nor is attributing economic harms and political sentiment to NAFTA in isolation to China.

The other thing is that a lot of the debate is toward explaining voters turning toward Republicans. But the crazy thing is that Republicans have been consistently more supportive and ideological about free trade than Democrats. Most of the opposition to NAFTA and China MFN was from Democrats (although they happened under Clinton's watch and with his support). The votes were significantly partisan, with Republicans supporting in much larger numbers - and that was true for all the trade deals and economic globalization policy in the following decades. It just doesn't make sense at all that voters mad about free trade/NAFTA/China would turn to Republicans; unless they were somehow sublimating their unhappiness into other issues or they were badly badly misinformed.

Being mad about NAFTA (or China trade) and then voting for Republicans didn't make any sense at all until 2016 with Trump. Even then, it wouldn't explain supporting most other Republicans who had previously supported free trade.