The Nordic Countries Use Market Power to Make Equality

A great primer on the Nordic economy and welfare state, with interesting comparisons to the USA and UK.

Here are the Nordic countries.

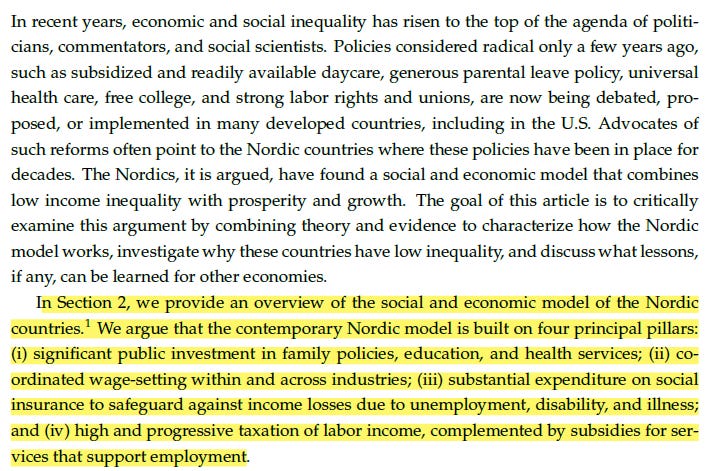

Many policies that were once considered quite radical - like universal healthcare, affordable childcare, and free college - are being debated among circles in America’s left. The Nordic countries are almost always held up as the exemplar for a strong welfare state with cradle-to-grave protection. Well, say Mogstad et al., let’s take a serious look at these countries!

The highlighted section shows what Mogstad et al. focus on as the core of the Nordic model. Spoiler, it’s (ii), or the strong wage compression via labor market institutions, that keeps the Nordic countries’ inequality low.

Three key points about the Nordic countries’ low inequality:

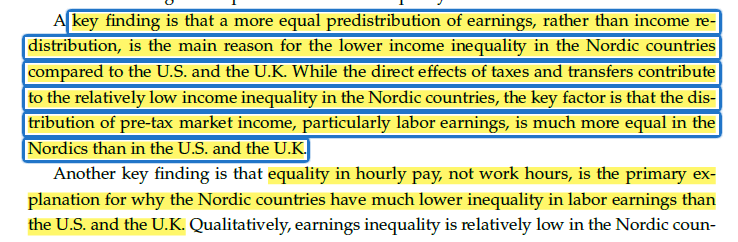

Predistribution - e.g. earnings before taxes and transfers - are the key. It’s not work hours, it’s pay rate, that matters most, and the big bang-for-buck includes inequality among men and women, not necessarily an equality of earnings across gender.

Market power that reduces inequality before any taxes, transfers, or social programs is the key. The authors compare this input to others - such as generous daycare policies, progressive taxation, and aggressive social programs. Those are great things to have that improve the quality of life in the Nordic countries, but they aren’t the things that reduce inequality.

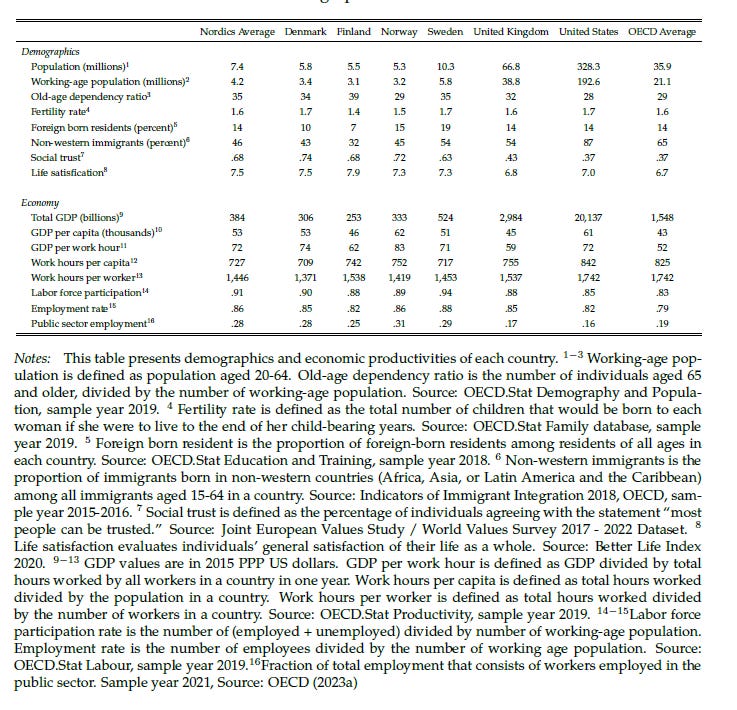

What are the Nordic countries, and what do they look like? How do they compare to the US and the UK on the fundamentals? A nice summary table:

Denmark, Finland, Norway, Sweden. Small populations, healthy and educated populations, trusting, happy, with GDP per work hour (not capita), and high public employment.

The key features of the Nordic countries: the welfare state, which is big, robust, universal, generous.

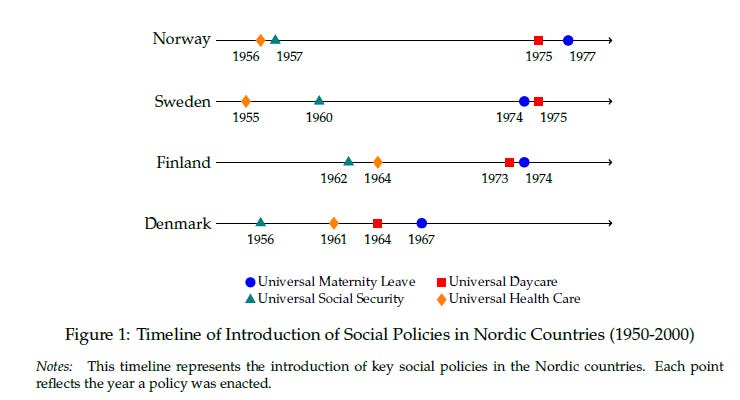

Most of the big welfare state pillars were established during the “Golden Age” of the welfare state, the 1950s.

I find some of the welfare state policies, sketched in Table 2 below, in the Nordic countries just bonkers. Massive investment in children, education, parents, families.

Another key feature: family policy, mostly parental leave and subsidized daycare.

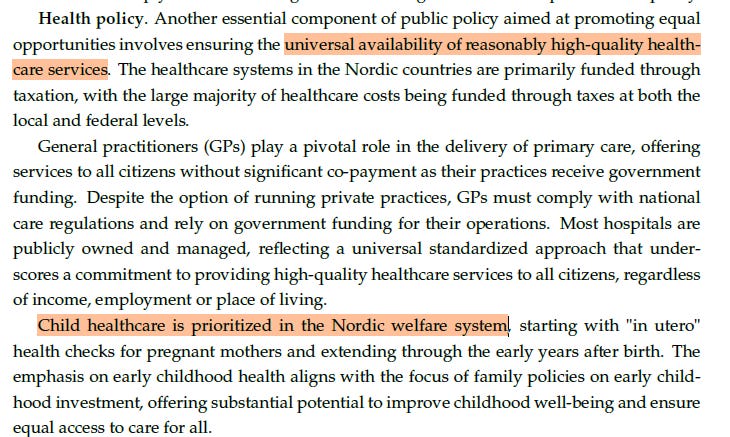

Another key feature: healthcare. I really like the Nordic countries’ focus on healthcare. In the USA, our policies seem to be organized around access to health insurance, which only occasionally aligns with healthcare, and healthcare only occasionally aligning with quality healthcare.

Another pillar: free, publicly funded education. Sure, this increases education, but I don’t understand how this policy will effectively turn education into a bludgeoned scarce good in which the most prestigious education degrees get to hoard all the status and money. So. weird policy (I’m being sarcastic and snarky here, if you can’t tell!).

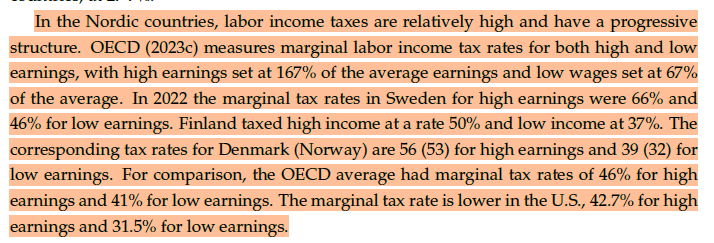

Another key feature: progressive taxation. Nordic countries have progressive tax rates (e.g. higher rates among higher incomes).

A key feature I hadn’t appreciated was the participation rate:

The y-axis is the inverse of the participation tax rate - so lower values means that tax rates make it more sensible to stay unemployed. Yet Nordic countries maintain employment via generous labor market participation subsidies (like childcare) that makes employment more “worth it.”

There are also layers of social insurance programs that eventually culminate in needs-tested last resort protections for folks who can’t stay in the labor market.

The Nordic system also has an interesting operation of the labor market.

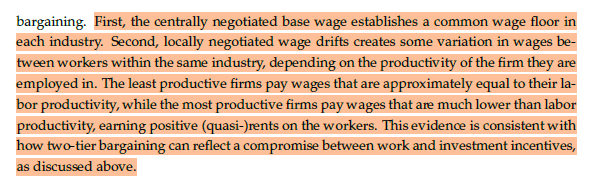

There is a two-tiered system of wage bargaining:

So tier 1 - a sector level bargaining (e.g. all fast food figures out a minimal acceptable pay rate for line cooks), then tier 2 is the local bargaining at specific workplaces, under these broader parameters. The US only kind of has this tier 2.

This multitiered system makes the decline of union membership less relevant in the Nordic context than the US context.

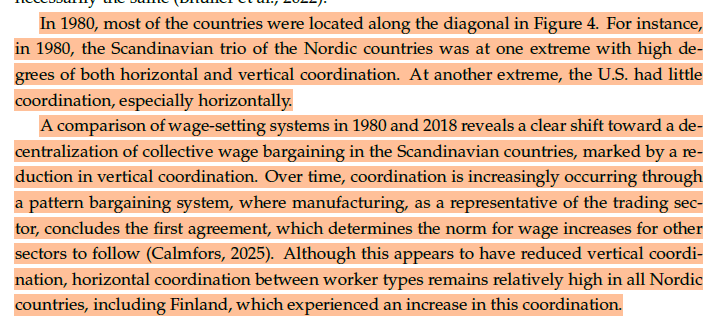

An interesting change to Nordic wage bargaining has occurred over the past 40 years - bargaining has become more decentralized (e.g. more to the firm level) but remains relatively coordinated (e.g. a high degree of bargaining coordination across different types of workers).

So the Nordics have shifted down from very centralized to some sectoral coordination. But they stay much more coordinated across different types of workers. The US, notice, is about as threadbare as you can get.

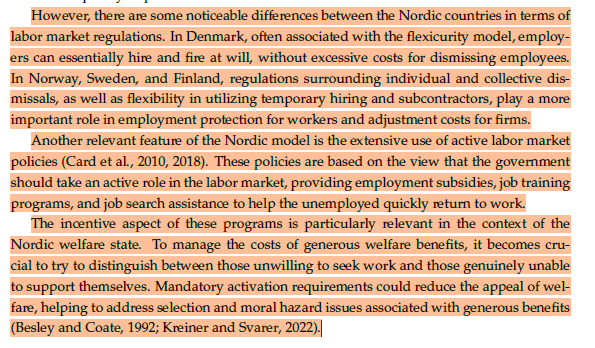

Two caveats - there is a lot of variation across Nordic labor market types. And with the intense government involvement in the labor market, a number of policies are taken up to make sure employment stays up.

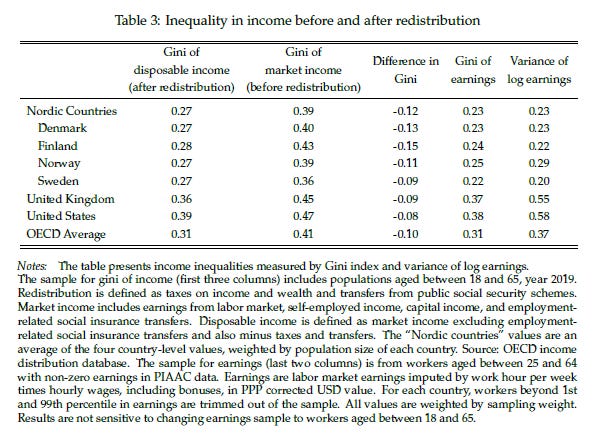

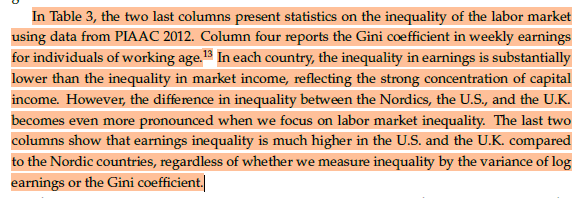

So what matters for the low Nordic inequality levels? Mogstad et al. make a strong argument for the “predistribution” or the labor market coordination that keeps inequality low before any tax or transfer or welfare state intervention. We can see what they’re talking about in Table 3.

The first two columns are inequality measures (0=perfect equality, 1=perfect inequality) of income after and before redistribution. Redistribution accounts for about 1/3 of the inequality difference between the Nordics and US/UK. Pre-redistribution inequality levels the other 2/3.

If we look just at the earnings of those employed (last two columns), the pre-redistribution gaps are even more stark.

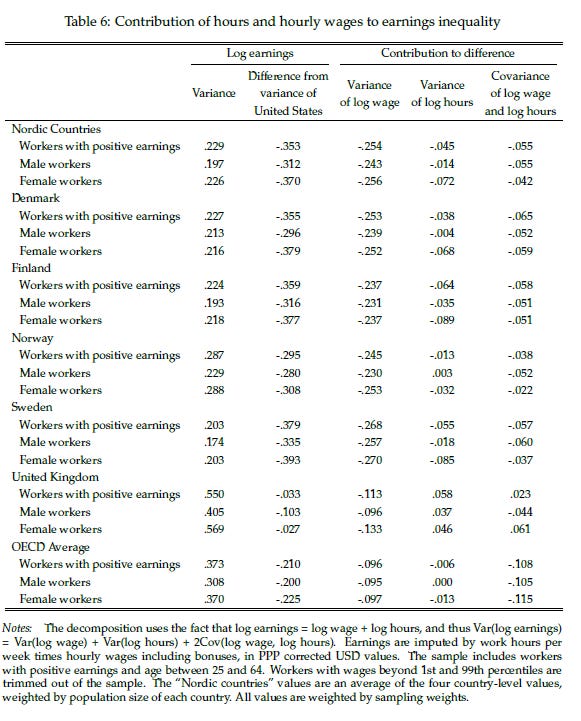

There’s less variability of work hours in Nordic countries, which will contribute to lower overall inequality.

A massive table, but look at “variance” columns, and the “Nordic Countries” and “United States” rows. USA has a good deal more variability in work hours. This will necessarily increase inequality in the USA relative to the Nordics…

…AND the USA / UK have higher wage inequality (e.g. earnings per hour worked) than the Nordics. The P90/10 is a decent wage inequality measure. It’s about twice as high in the US than in the Nordics.

While both hours worked and wage inequality contribute to the gap between the Nordics and the US, it’s mostly a wage inequality story. Mogstad et al. decompose earnings inequality gaps between countries. Of the 0.353 difference in earnings inequality between the Nordics and the US, .254 comes from the difference in wage inequality levels. So … most of it.

They look at the contributions of gender equality - and there isn’t much there. Most of the Nordic / USA gap occurs due to more equal wages within genders, not more equality of wages between men and women in the Nordic countries than the US.

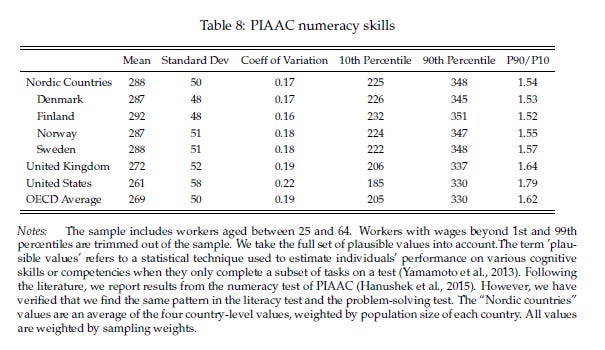

Why low wage inequality in the Nordic countries? Well, this being an economics paper, the main question is whether this is a skill issue. The authors use PIAAC data (PIAAC is a cross-national survey that collects a variety of basic skill information from representative samples of a country’s adult population).

Low skilled Nords are quite a bit more skilled than low skilled Americans. And high skilled Nords are a bit more skilled than high skilled Americans. The gap in skills (P90/P10) is lower in Nordic countries than in the US or the UK, but only by a bit.

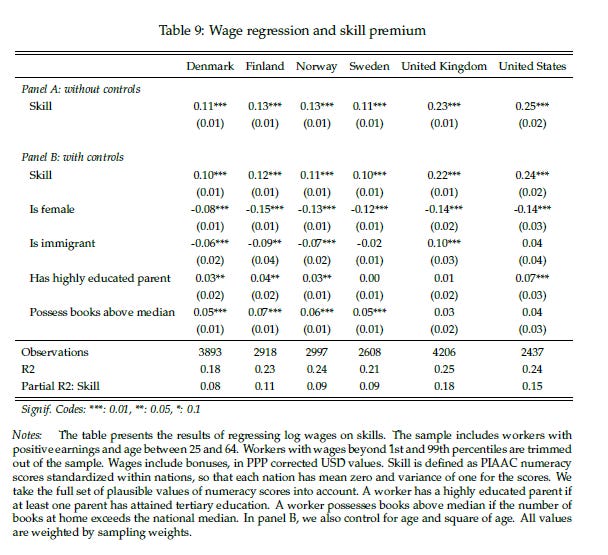

Returns to skill, however, is much more compressed in the Nordic countries than in the USA or the UK.

Look at the “Panel B” section of this table, and the “Skill” row. This shows the predicted wage returns to an increase in the skill measurement in the PIAAC. The returns to skill are about twice as high in the USA than in the Nordic countries. Remember - this isn’t about there being more skilled people in the USA, and the inequality of skills is only a little higher in the USA than in the Nordic countries.

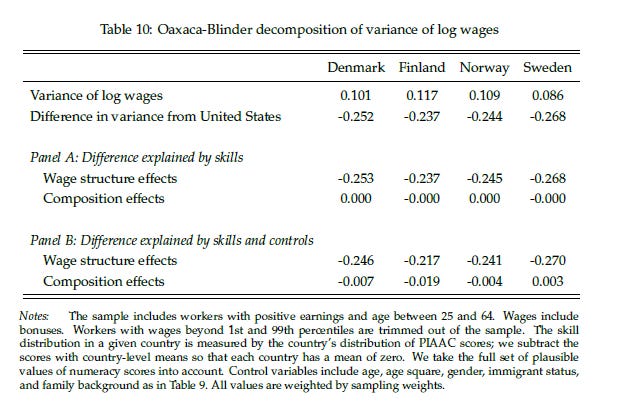

In fact, if you break apart the distribution of skills and the returns to skills in the USA and the Nordic countries, you see that the contribution of skills to inequality is entirely a “returns” story, and an almost zero “composition” story.

They also replicate this finding by years of schooling. Again, it’s a returns thing, not a composition thing.1

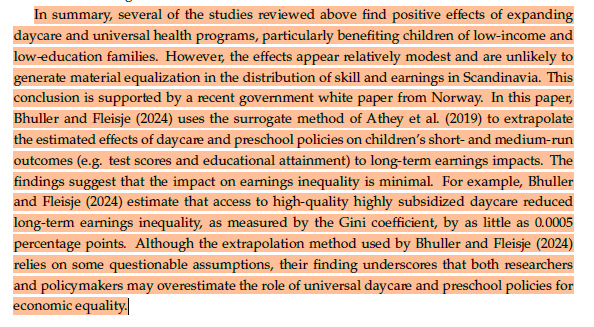

Nor are these gaps simply attributable to things like healthcare and daycare welfare state policies.

The authors return to wage setting coordination and discuss how the Nordic approach might keep wages compressed.

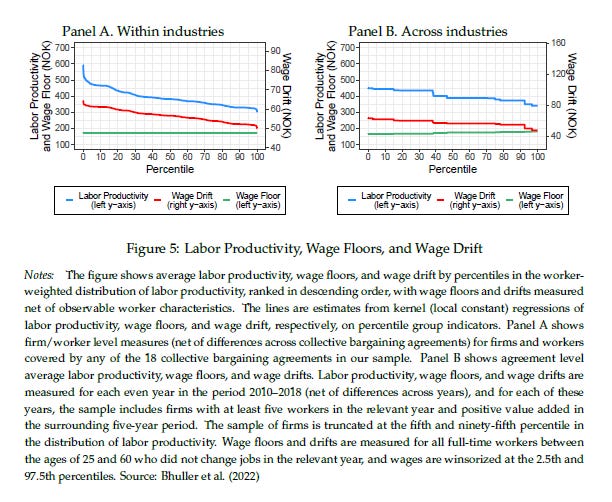

Essentially, the Nordic system kind of provides a decent high floor while also incentivizing productivity by allowing for firm-specific higher payoffs to productivity, relative to worker productivity.

This results in wages that are more compressed relative to the distribution of productivity.

A big question is … would this equality of wages ramp down productivity in the long run? Skilled workers and entrepreneurs like big payoffs to their work. On the one hand, we have the free-rider hypothesis, where the Nordic system will gunk up productivity, dynamism, and entrepreneurship. On the other, the authors proffer the idea that the Nordic system might actually boost up productivity and dynamism, especially in the long run and in post industrial rich democracies:

Strong union and government action can also incentivize companies to invest in labor saving technology, which will increase productivity.

Presumably, as long as firms and governments don’t abandon workers wholesale, this productivity investment can be mutually beneficial to labor and capital.

Both theories are speculative. And suffer from:

More work to be done. But I find this theoretical horserace very compelling.

Mogstad et al. end with the following:

I had intended to only do a brief summary of this paper along with a set of others. But the more I started to summarize it, the more I loved each part. So it gets its own showcase!

Some General Thoughts

I love this article and I love how thoroughly and systematically it unpacks the institutional context of the Nordic countries compared to the USA. A few random thoughts, which when combined with $4 will get you a cup of coffee:

Wage coordination and union coverage seem to be the names of the game. There is some energy to revitalize the labor movement in the US, but normally I see this kind of talk occurring within the structural logics of the US’ fragmented and fractured labor system. I think such efforts are likely doomed to fail. The name of the game is probably re-institutionalization. But that’s really hard.

Covid probably provided the opportunity to re-institutionalize. And we completely dropped the ball. To quote the internet, “epic fail.” Bummer.

I think that any attempt to “Nordify” the US will likely be seen as a loss among our system’s big winners - the big earners among the college educated, which will involve folks like tech employees, successful grads from prestigious colleges, certain STEM workers. That’s a coalition with a strong grasp on the American imagination. In fact, lots of current culture war topics can be seen as a fight among this group. A mobilization to make all such folks feel like they’re losing will be painful and receive a massive swing back. Low probability of success, but would yield longer term benefits, I suspect.

Trust is higher in the Nordic countries, and I worry that a general libertarianism is preferred across the American cultural and political systems over what it would take to increase trust. Part of trust, I suspect, is a reunification of behavioral and cultural norms. Part of increased trust, I suspect, would involve a general reduction in crime and disorder. When the rubber hits the road, I would suspect that a supermajority of Americans would not like what it takes to transition to a high trust society. Big lift.

Mogstad et al. are kind of hard on the social insurance and welfare programs in the Nordic system. I suspect these have disproportionate payoffs in culture and wellbeing that are difficult to measure.

The USA is really, really big. That geographical distance will make coordination difficult.

There is a deep system of laws and regulations that make a Nordic style of coordination difficult. On the one hand, I love the idea of going FDR and radically transforming that deep system for longer term benefits. On the other hand, such a set of activities would likely also pave the way for strongman responses. A big “no risk it, no biscuit” proposition. But you don’t always get the biscuit.

The big payoff to the American system seems to be growth, a broad level of wealth not appreciated by its people, coupled with low community and a wild and dangerous style of life. To me, the tradeoff doesn’t seem worth it. Growth might not be very broadly beneficial these days. And relative standing really undercuts the sense of improved wellbeing wealth should bring. But I admit that there are lots of people who are into the wild, dangerous, and lonely lifestyle.

Generally, the Nordic system seems like it’s organized towards the broad life of human beings. I am increasingly feeling that the benefits and features of the American system are anti-human. For example, these days it feels like America’s tech innovations are somewhat opposed to the idea that humans are good and worth cultivating. But that might be overly optimistic and pessimistic of the two systems.

I am curious about the ability of the Nordic system to build things. Do Nordic societies have housing shortages? Are they too slow and sclerotic to build new things? Does the Nordic model provide a more fundamental road to abundance than the recent push proposed by Ezra Klein and Derek Thompson?

I am seeing more center-left thinkers take critical stances towards American labor unions - folks talking about Biden’s loyalty to unions as a major policy drag. Klein and Thompson describing unions as a major impediment to building things. A variety of folks, like Matthew Yglesias, arguing that longshoreman are fundamental problems for port automation. I suspect that much of this framework occurs in America’s highly fragmented and isolated labor system. There seems like there should be a way for labor, productivity, growth, and building things to be straightforwardly coupled. I wonder if the Nordic system provides a way?

Productivity is the big blind spot in the sociological approach to stratification. This article shows that a deep understanding of productivity and its connections to things like earnings, inequality, technology, etc., yields a deeper understanding of stratification processes.

If I didn’t know any better, I’d say that all the talk by prestigious USA schools about equality, equity, access, and fairness was a tad disingenuous. But I know better than to question my superiors.

Over the years, I've seen repeatedly that "pre-fisc" inequality of the Nordics was pretty high, but it was all equalized post fisc. This paper argues otherwise - or that only 1/3 was post fisc. So, that's a surprise if true. I'll have to go and dig around on this to see if they're measuring things differently somehow. The data - on the table on the wikipedia page shows the nordics with moderate gini pre-fisc among OECD, but comparatively lower gini post-fisc which implies a higher than average tax/redistribution level of effort. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_countries_by_income_inequality?utm_source=chatgpt.com